The respirator mask worn in record numbers by healthcare professionals around the world in the midst of the Coronavirus pandemic began at the University of Tennessee--and with (formerly) retired researcher Peter Tsai.

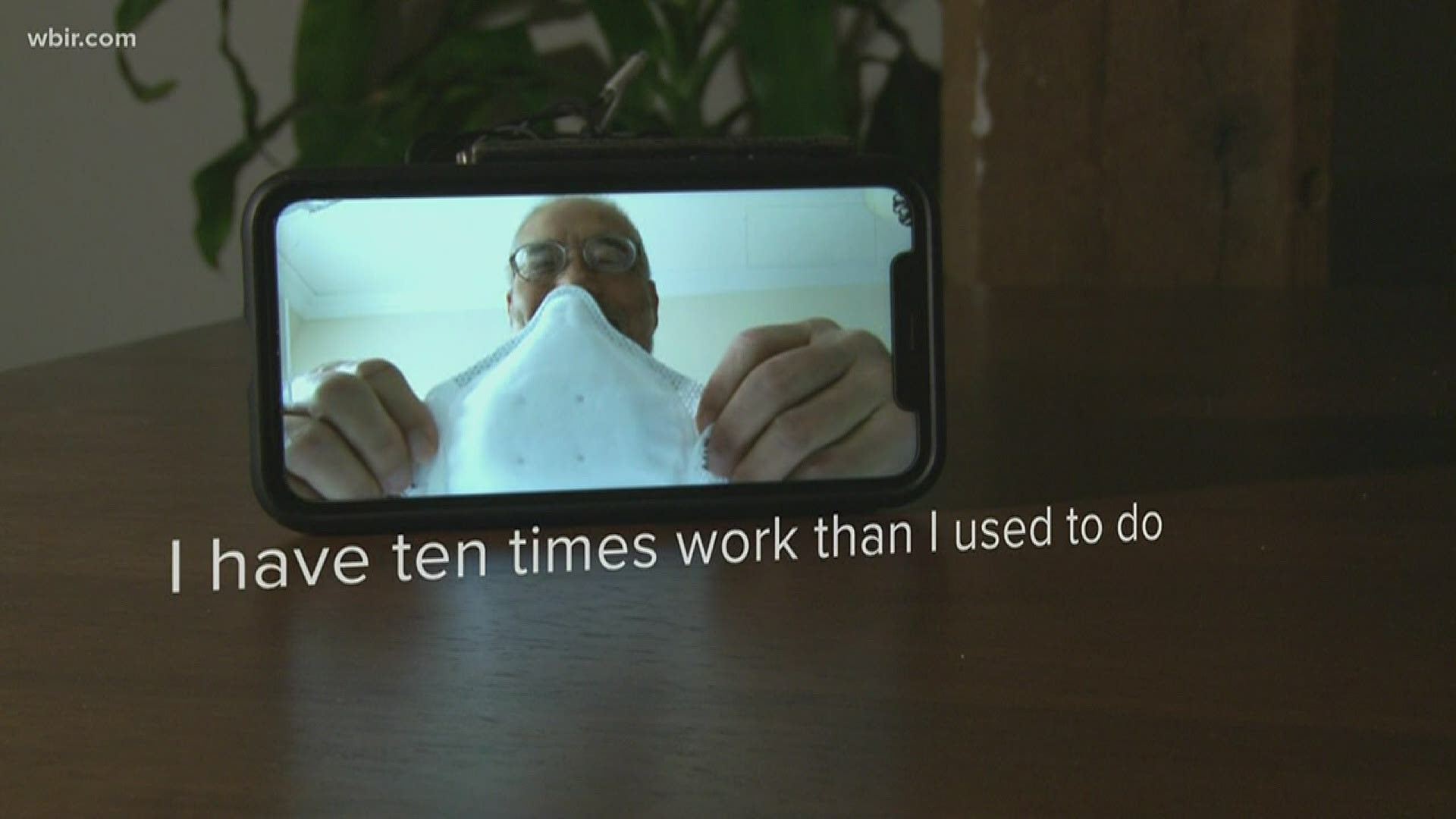

In the early 1990s, Tsai registered a patent on a special kind of electro-statically charged material used in N95 masks. Now, companies have asked him how to retrofit assembly lines to make more masks, and he's studying how to safely sterilize masks so they still work if doctors and nurses have to use them more than once.

"We did not expect this N95 respirator be used for so many people," Tsai said. "I feel that I have more work to do."

The N95 mask's physical pores are bigger than particles like the coronavirus, but Tsai's invention changed things. He figured out how to add static electricity to the material. That, in turn, attract the particles and stops them from going through.

"In this way, the filtration efficiency is ten times improved than the uncharged media," he said.

His invention makes the mask ten times more efficient. It's what makes it an N95 able to filter out 95 percent of particles.

But when Tsai designed it, he did not have virus particles in mind.

"This respirator, N95, was originally for construction workers," he said.

Medical authorities decided it could also be useful for preventing virus spread. Now the inventor whose mask keeps doctors safe finds himself busy once again.