Great Smoky Mountains Natl. Park — Drawing millions every year, the Great Smoky Mountains is the United States' most visited national park.

Its third-highest peak, Mount LeConte, is a big attraction among dedicated hikers with reservations at the famous LeConte Lodge booked out months in advance.

From 6,593 feet up in the mountains, it’s hard to imagine that a century ago Mount LeConte was also one of the park's only bastions of wilderness amid the march of the industry.

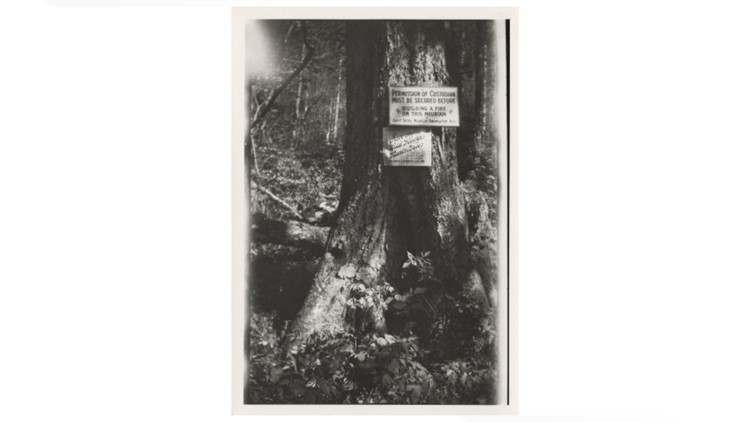

"There had been so much logging that had gone on in southern Appalachia, and LeConte was one of those areas that still looked relatively untouched," said Michael Aday, the librarian-archivist at the Great Smoky Mountains Collections Preservation Center.

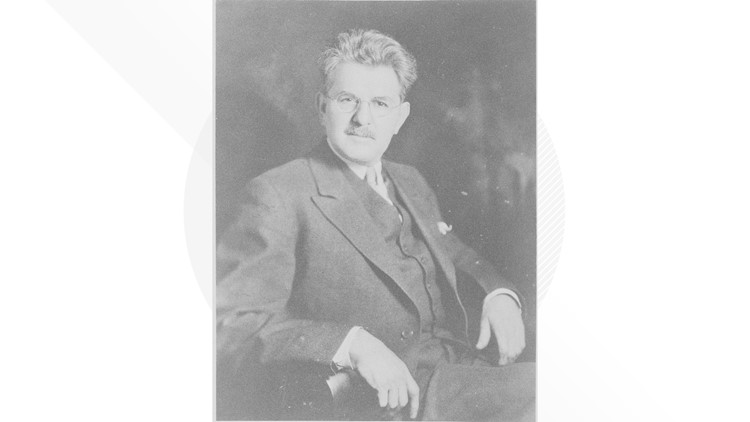

In the early 1920s, the North Carolina-based Champion Fibre Company owned the mountain, but Colonel David Chapman with the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association saw an opportunity as the group advocated turning the logging-scarred Smokies into a national park.

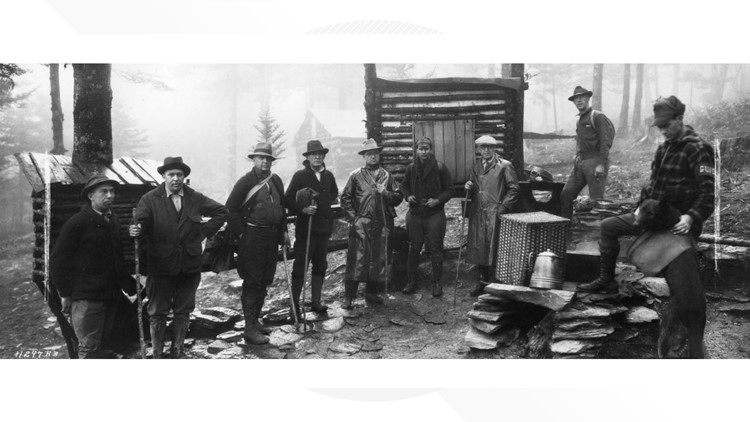

In the summer of 1924, the conservation association was trying to get the Southern Appalachian Mountains Commission to visit the Smokies and consider it for national park status.

"They had declined to come until Chapman, basically, you know, just begged them to come just take a look. And when he did, he planned a trip up there for all these people to stay," said Ken Wise, the retired co-founder of the University of Tennessee Libraries' Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection. "When they got on Mount LeConte and got up on Cliff Top and took a look, then it was automatic. This was going to be a park."

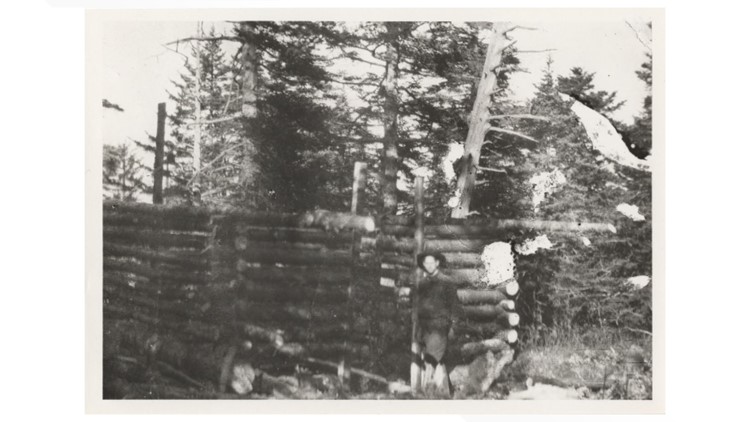

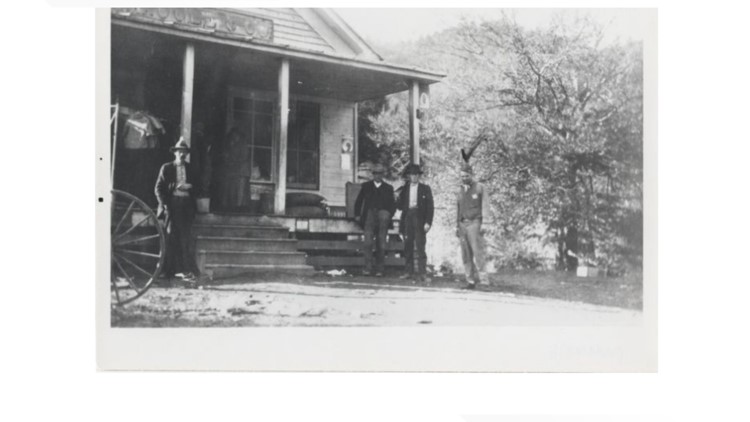

With the visit a success, Chapman and the conservation association struck a deal with the Champion Fibre Company to eventually buy the mountain. One of the first orders of business was building a permanent camp for visitors.

"The Great Smoky Mountains Conservation was trying to procure that land for a new national park. They wanted somebody up on LeConte to keep sanitary conditions and to build a cabin for people to visit and just take care of the area until they could take possession of the mountain," Wise said.

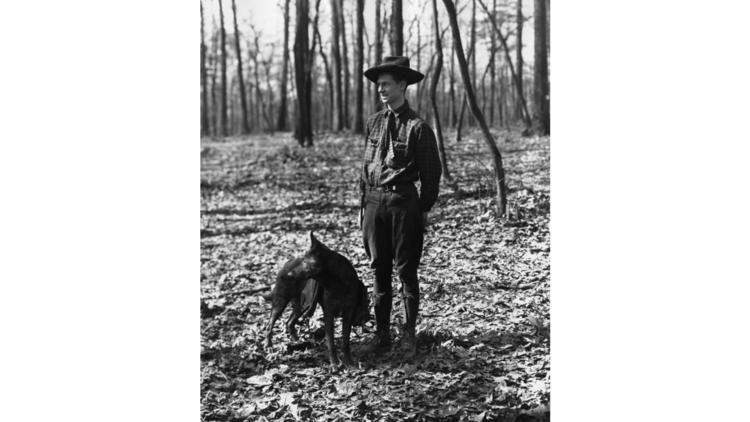

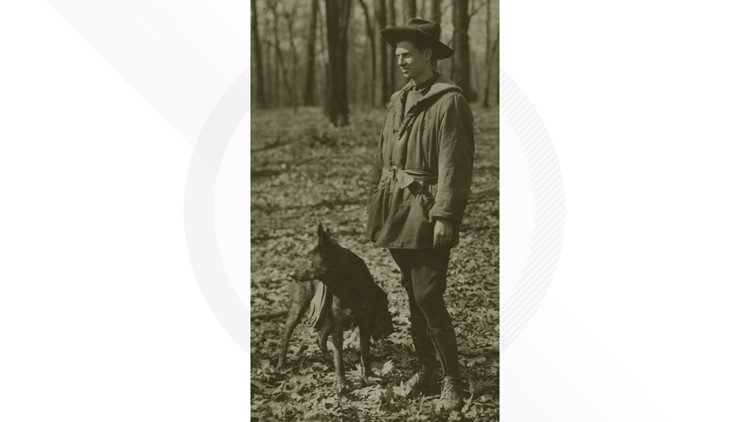

A 24-year-old from Knoxville caught Chapman’s attention. By the time the association recruited him, Paul Adams was already an experienced outdoorsman, serving as an assistant scoutmaster for a Boy Scout troop and co-founding both the East Tennessee Ornithological Society and the Smoky Mountains Hiking Club.

This new job would send him to the summit of Mount LeConte for nearly a year starting in the summer of 1925, but Adams' mother did not like the idea of her son being alone in the mountains.

"She knew that he was going to be living on Mount LeConte in a very isolated situation for several months out of the year, and she wanted him to have a companion and she recommended that he should get a dog," Aday said.

As fate would have it, a friend named Russell Smith was taking care of a police dog after its owner, a Knoxville detective, was killed in a gun battle. He invited Adams over to meet it, and the pair seemed to bond instantly.

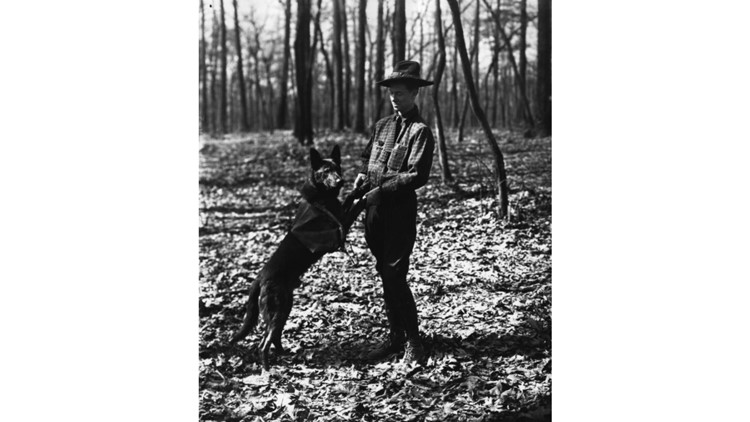

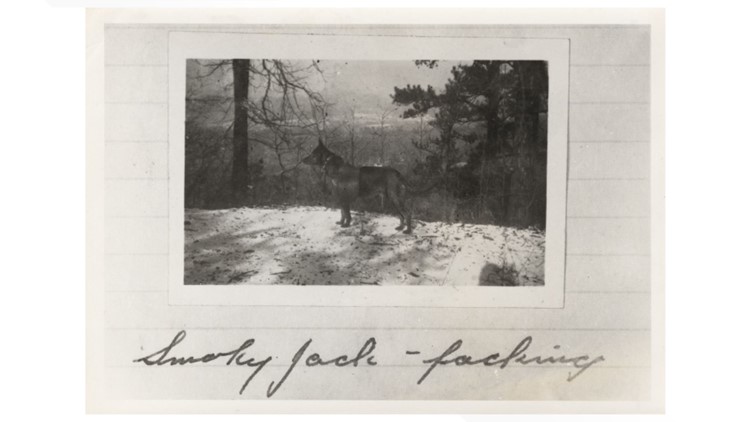

With some negotiation, Adams bought the black German shepherd named Cumberland Jack II of Edelweis for $250, equal to roughly $4,400 today, which he would pay in installments.

Wise said Adams gave his canine companion a new name to match their mountainous home: Smoky Jack. He recognized the dog’s intelligence with his prior police training and knew Smoky Jack could be more than just a friend atop LeConte.

"David Chapman, who was a World War I veteran, told him about the U.S. Army and the cavalry, how they took dogs and trained them to run dispatches behind lines in France in World War I. So Paul Adams decided that he would be able to train Jack to do something similar," Aday said.

Keeping with the military inspiration, Adams went to an army salvage store in Knoxville to gather supplies and a new piece of gear for Jack.

"He had a set of saddlebags made for the dog," Wise said.

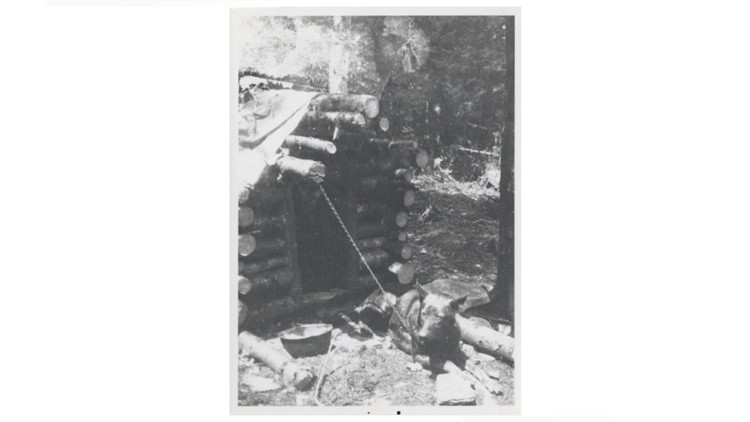

The saddlebags, originally intended to fit over cavalry horses' saddle pommels, gave the German shepherd a new purpose.

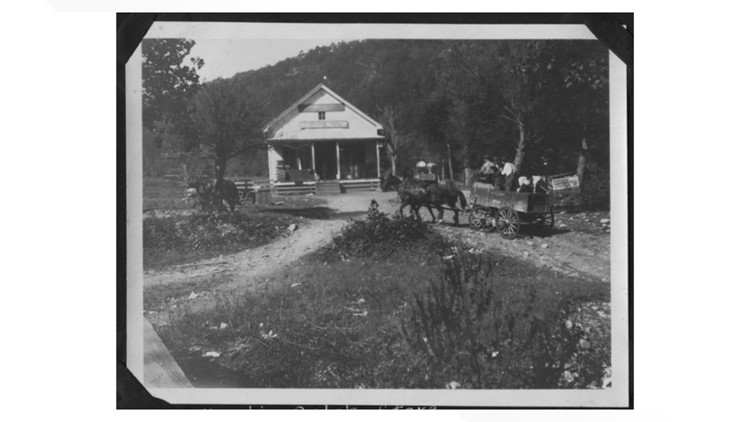

"[Adams] trained Jack to go from the top of Mount LeConte, all the way down to Ogle’s Store in Gatlinburg. And he would put a note, a shopping list and some money in the bags," Aday said. "Mr. Ogle was the only person who could actually handle the dog. And so he would take the money and put nails or flour or whatever it was Paul happened to buy at that time, put them in the saddlebags, put the change in there and the dog would run right back up the mountain."

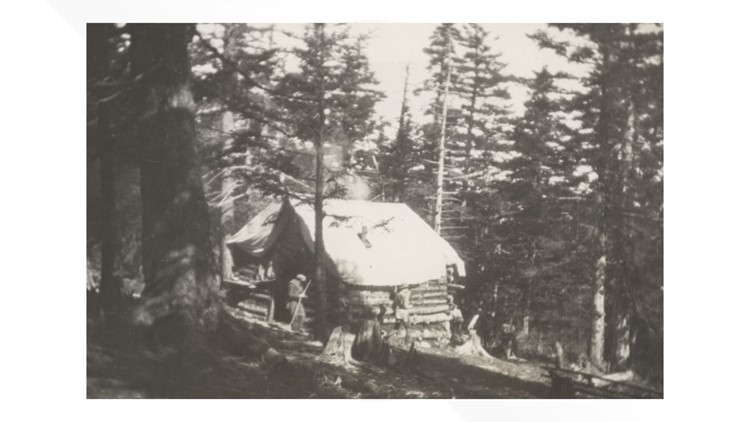

For nine months, Smoky Jack made the trek on what is now Rainbow Falls Trail, carrying up to 30 pounds at a time, while Adams built the first permanent camp on Mount LeConte.

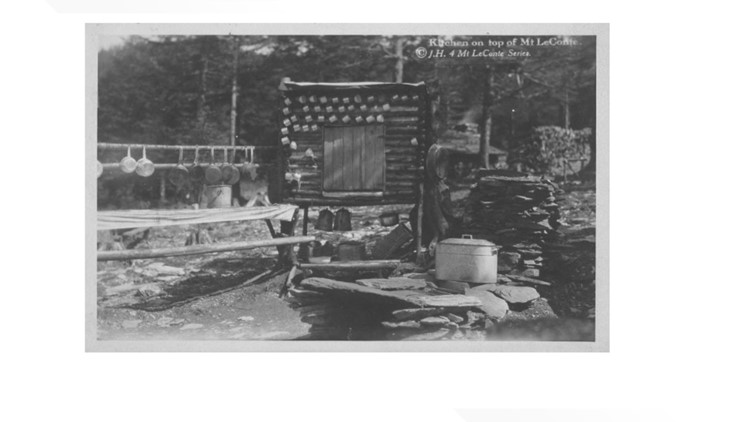

"It was a very crude, sort of a balsam log lean-to with an outdoor kitchen," Aday said.

Adams documented their adventures atop LeConte in journals that were later turned into novels entitled "Mount LeConte" and "Smoky Jack."

Some stories recounted the dog’s heroics like the time he helped Adams back to camp after a fall in Huggins Hell, an especially rugged stretch of land near Alum Cave Trail.

"They got on a rather narrow ridge, kind of a knife-edge ridge, and Paul fell off. And he was knocked unconscious. And when he wakes up, his water bottle had broken, he hit that hard, but the dog is still there," Wise said.

Others detailed the lengths Adams went to in breaking Jack’s bad habit of killing chickens on homestead farms on his way up and down the mountain.

"Paul took one of the chickens that he had to buy and took a piece of wire and wrapped it around the dog's neck and let it rot for a week. And then that cured Smoky Jack from wanting to kill the chickens on the way up," Wise said.

Another recalled the time Smoky Jack used his police training on the trail. A man approached Adams on his way down the mountain, pointed a gun at his back, took all of his money and told him to wait for several minutes without turning around.

"He never got to see the man. He was always behind him. Well, a few days later, they're down at Charlie Ogle's store, Smoky Jack and Paul Adams and several people around there, and a man comes in and the dog identifies him. And so he pins him against the wall or whatever, and the man confesses that, you know, he took the money," Wise said.

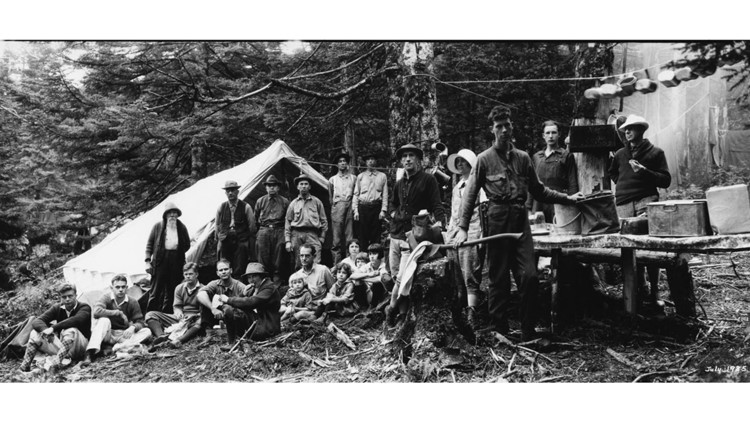

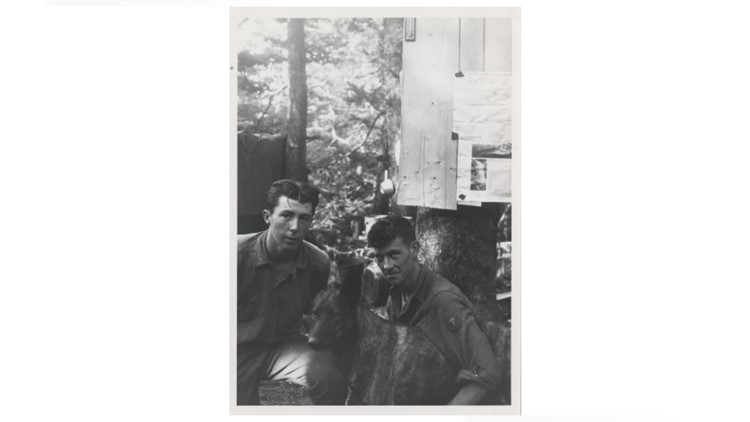

Photos: Building the first camp on Mount LeConte

The pair also popped up in newspapers with headlines heralding the “Young Man of Mountain” and his “fine German police dog.”

Beyond his work on the camp, some articles celebrated the rare birds Adams discovered at the summit and shared the intimate details of his life in the mountains.

"It really is sort of the first chapter of the story about Great Smoky Mountains National Park," Aday said.

Despite the praise, spring 1926 spelled an early end for the duo’s time on Mount LeConte.

"Paul Adams got fired after the first year. We don't know why. It may have been he just didn't quite have enough experience to run a camp," Wise said. "It was taken over by Andy Huff’s son, Jack Huff, who built what we now have, the LeConte Lodge."

Adams and his saddlebag-wearing sidekick stayed in the Smokies for a little while longer working as guides before moving to Alpine in Middle Tennessee and eventually settling in Crab Orchard in Cumberland County.

"He changed the dog's name back to Cumberland Jack," Wise said.

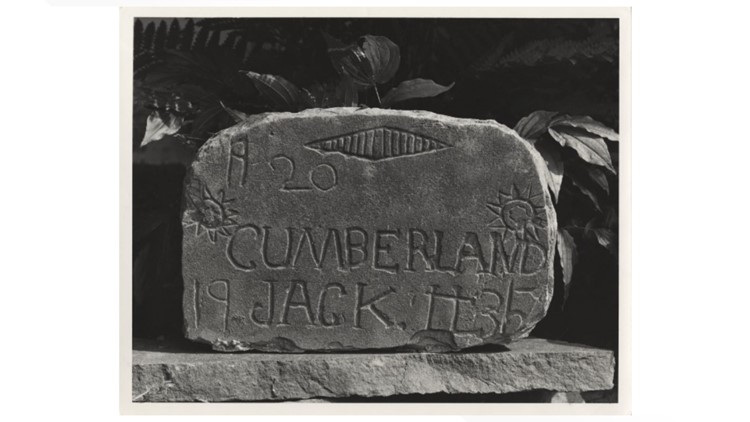

Cumberland Jack stayed at his partner’s side for nearly a decade more, living to the ripe old age of 14. Adams buried his constant companion on his land with a special headstone, which read "Cumberland Jack II 1920-1935."

He ventured to the top of Mount LeConte a few more times without his beloved German shepherd, including a hike in July 1975 to mark his camp's 50th anniversary when he was 74 years old. Adams continued his work as a celebrated naturalist until his death in 1985.

Though their time on Mount LeConte was brief and the camp they built no longer stands, Adams and Cumberland Jack still have a foothold in the park’s foggy foothills.

"Cumberland Jack and Paul Adams are revered legendary figures in the history of the Smokies," Aday said.

The Great Smoky Mountains Collections Preservation Center in Townsend houses two of the few surviving relics of their work: a photo of the trailblazing duo and Jack's saddlebags.

Aday said the bags are popular among tour groups and hold a deeper meaning in the park's history.

"This is sort of a physical representation of the work and the minutia that went into building support for establishing a park in southern Appalachia," he said. "From little acorns, mighty oaks grow, and this is an amazing little acorn that we have in the collections."

Beyond historical archives, their adventures come alive in print.

"Paul Adams is a fixture in the lore of the Great Smoky Mountains," Wise said. "And the dog is just probably the most fascinating part."

Wise, who co-edited the book “Smoky Jack” based on Adams’ writings, said it acts as a period piece for a pivotal point before the park.

"This book has these episodes with really good human interest happening in the Smokies at that critical time when we're trying to decide if it can be a national park," Wise said.

Cumberland Jack even inspired a Gatlinburg restaurant's name, Cumberland Jack's LeConte Kitchen, with his story on display inside.

Whether it’s pinched in well-worn leather, printed on a page or even presented on a Gatlinburg eatery, the legacy Paul Adams and Cumberland Jack left behind lives on with the millions of visitors who come to the Great Smoky Mountains every year, and, perhaps more so, with the adventurous hikers who reach the top of Mount LeConte.

"I shudder to think what this area would look like without Paul Adams, David Chapman and all those other people who helped to establish this park. We owe a debt of gratitude to those people, I really think," Aday said.