JEFFERSON COUNTY, Tenn. — With school starting back up, one Jefferson County student had to wait weeks for an important textbook to arrive from out of state.

This doesn't seem like a big deal, except it's a calculus book and it's written in Braille.

Campbell Rutherford is a home school student in Jefferson County.

She started homeschooling with a teacher for the visually impaired was no longer available in the local school district.

Campbell was born blind and has been reading braille since she was 3 years old.

"I rely completely on braille and screen readers to access the printed word," she said.

Campbell is so used to reading Braille, that she's placed almost every year in state Braille reading competitions and even competed at nationals.

So naturally, she'd like to be able to read her textbooks in Braille.

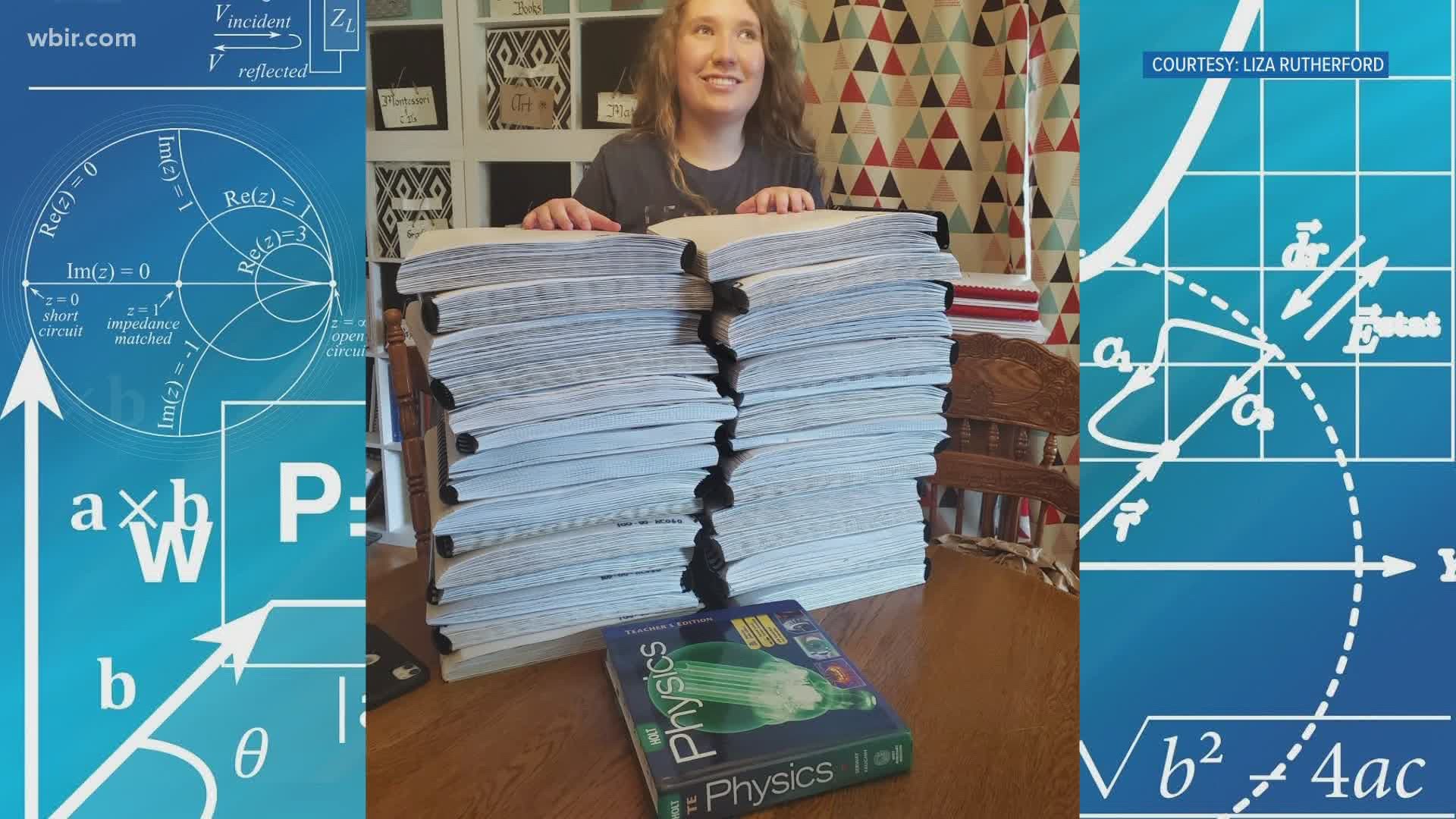

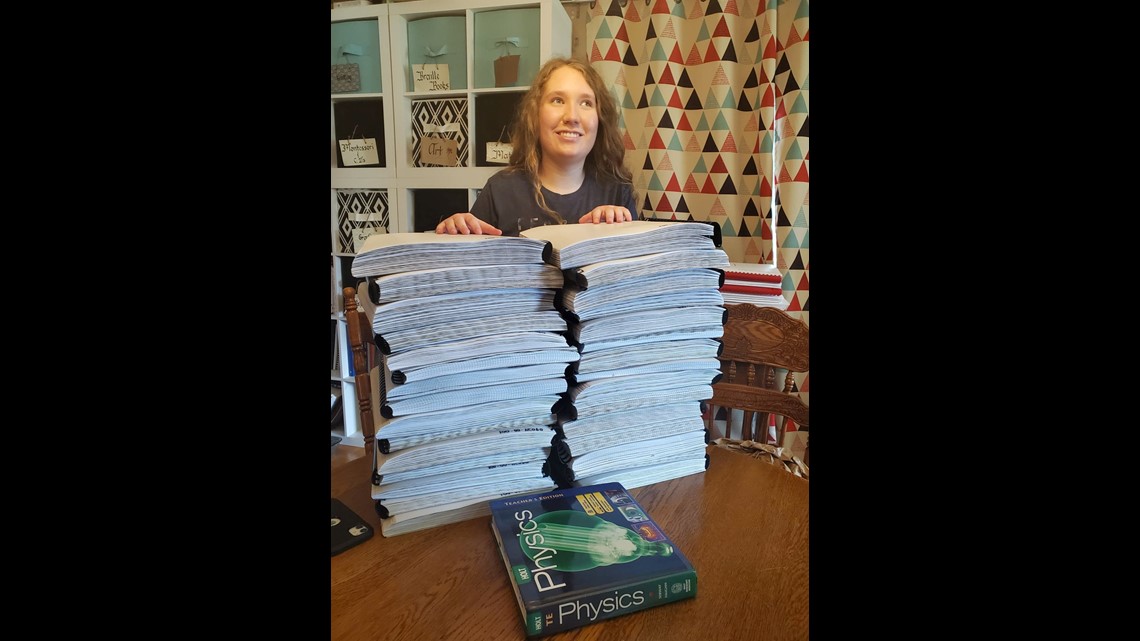

Because each page has to be embossed with the Braille indentations, Campbell's textbooks are huge.

Here's her AP physics book. All these binders are one book, containing everything in the print book next to it, just in Braille.

"I used to have to borrow a truck to go get her books," said her mom, Liza Rutherford.

These books are so much bigger because Braille has to be big enough to be felt by the fingertips of the reader.

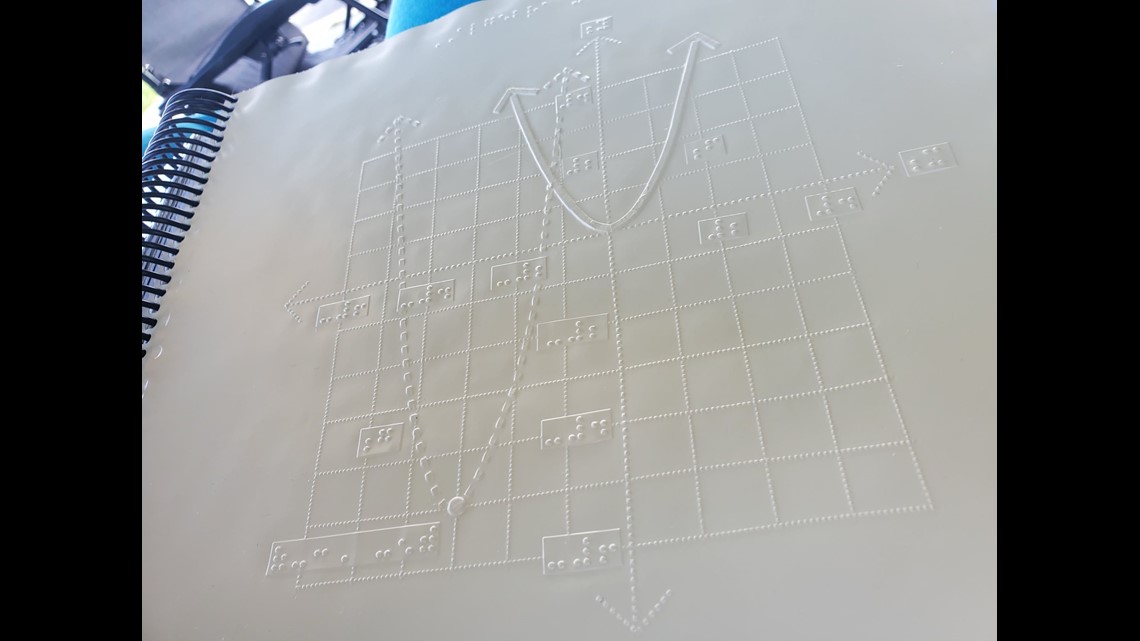

While a standard physics book may have four graphs on one page, they have to have their own pages in Braille.

The National Braille Press reported only about 12 percent of blind school-age students can read Braille, making it difficult to access advanced textbooks.

There were no Braille AP calculus books in the state of Tennessee.

The Rutherfords worked with the Tennessee School for the Blind to find this 20-year-old edition from Maryland.

Campbell said oftentimes visually impaired students are discouraged from taking hard courses.

"I have friends that, when they're struggling with math they've been told, 'it's okay that blind people aren't good at math typically,'" said Campbell.

Campbell plans to major in math in college and go into epidemiology.

She said it's those low expectations that hinder her and others the most, not her lack of vision.

"We even had an administrator at one point come to me and say, 'does Campbell really need a high school diploma for her adult life?'" said her mom Liza Rutherford.

"That's probably the one that's infuriated me the most over the years," said Campbell.

The National Federation for the Blind reported only 31.6 percent of people who are blind have a high school diploma or GED.

The Rutherfords believe a shortage of teachers for the visually impaired adds to this problem.

They are hopeful that as technology spreads, more blind students will have the educational access they need.

"There are other ways of doing things besides the sighted way or the able way," said Campbell.

She's connected with a blind math professor from Connecticut who can help her if she has any questions in the course.

Campbell plans to take AP physics, and hopefully AP calculus, with a proctor next spring who will describe the graphs to her and record her multiple choice answers.