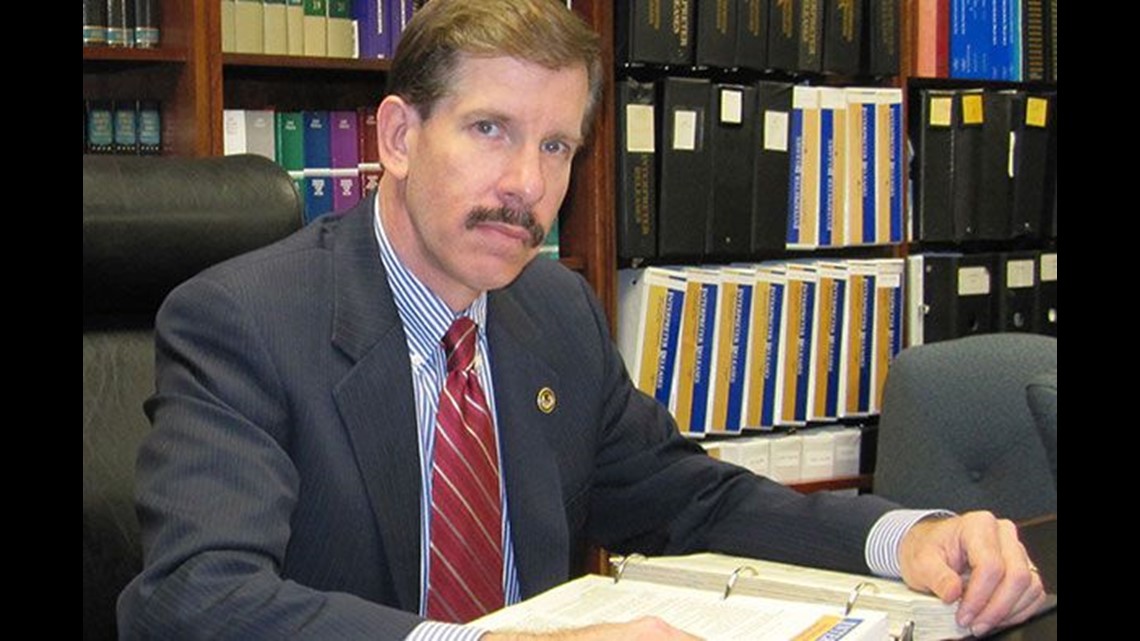

KNOXVILLE, Tennessee — In years past, Eli Rosenbaum would have said there were still many people to deport from America who helped the Nazis carry out their horrific persecution of the innocent during World War II.

Today, however, the director of human rights enforcement strategy and policy for the U.S. Department of Justice thinks that time may be coming to a end.

Indeed, a 94-year-old Oak Ridge man could be the final figure of that era here in the U.S.

"It is possible this will be the last case," Rosenbaum told 10News.

Friedrich "Fritz" Berger, a German native, has been ordered removed by a U.S immigration judge after a two-day trial in Memphis.

His transgression? Judge Rebecca L. Holt found, as the federal government alleged, that Berger worked as a concentration camp guard in the waning weeks of World War II.

While he was not a member of the Nazi party, the fact that he took part in guarding prisoners held at a Meppen, Germany, subcamp, part of the larger Neuengamme camp system, is enough under federal law to force him out.

An office of the Justice Department has worked more than 40 years to identify people who ended up in America after aiding Adolf Hitler's torment during the war. Rosenbaum has been a key figure.

Among those who were flushed out is John Demjanjuk, a retired Ohio auto worker and naturalized citizen deported after the DOJ found he'd been a guard at the Flossenburg and Majdanek concentration camps where more than a quarter-million civilians were killed. Demjanjuk, born in Ukraine, is now dead.

The government has identified dozens of wartime "persecutors," a specific legal reference to those who played a part in helping the German effort.

Rosenbaum said there's no evidence Berger, who was 19 and a member of the Germany navy, mistreated prisoners. His participation as a guard, however, was enough under the law.

The key word is "persecution" on behalf of the Nazi regime, he said.

INDEX CARD IN A SHIPWRECK

Berger's attorney Hugh Ward of Knoxville said his client is appealing Holt's decision.

That process starts with the Board of Immigration Appeals in Virginia, and from there he can turn to the Sixth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals in Cincinnati. The final option: the U.S. Supreme Court.

Rosenbaum litigated the case against Berger with Susan Masling of the DOJ.

The office also pursues criminals from other international conflicts who end up coming to the United States.

Rosenbaum said deporting someone accused of atrocities or persecution is complicated.

"All of these cases take a long time to put together," he said.

Documents recovered from the war often play a part. The Nazis destroyed as much as they could when it became clear the Allies were going to prevail, Rosenbaum said.

But records still surfaced. For example, the Soviet Union found and kept many documents detailing Nazi schemes and personnel after Germany's fall that were later used to prosecute war criminals.

Rosenbaum said a single index card offered information about Berger's role as a concentration camp guard. It's the only document the government has with Berger's name and his ties to the Meppen camp, he said.

The card was recovered by German harbor police after they raised a sunken ship in 1950.

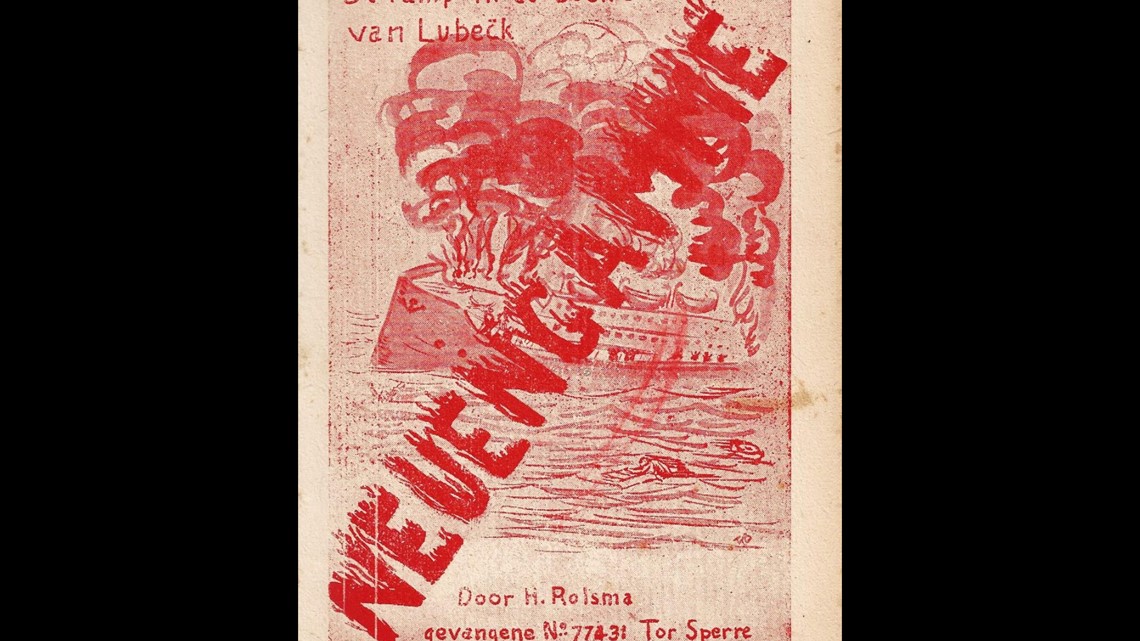

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and jewishgen.org, the British bombed the German cargo ship Thielbek in May 1945 as it sat in the Bay of Lubeck northeast of Hamburg.

The ship carried prisoners from the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg. The Germans planned to take the ship out into the Baltic Sea and sink it, thereby getting rid of evidence of the camp itself.

The British didn't know who was on board.

Nearby sat the large German ocean liner, the Cap Arcona. It, too, carried camp prisoners. The RAF also struck it.

"On May 3, 1945, when the ships were loaded but before they could leave the harbor, British aircraft flew over Lübeck," according to jewishgen.org. "Assuming that the ships were German transports, the British bombed the ships and they sank."

More than 6,000 prisoners died.

WAR ENDED 75 YEARS AGO

Berger declined last week to speak to 10News when contacted by phone. He lives on a cul de sac in Oak Ridge.

In March 1945, it was Berger's job to help escort prisoners -- Poles, Jews, Russians, the Dutch and other -- to worksites outside the Meppen subcamp, to watch over them at the sites so that they didn't escape and to take them back at the end of the day.

The camp near the Dutch border had a high death rate. According to the government, camp personnel subjected the prisoners to "atrocious" conditions.

Berger didn't ask to be transferred from Meppen, according to the DOJ.

He was there until late March 1945, Holt found, and also helped with a forced two-week march of prisoners in the closing days of the war to the main Neuengamme camp near Hamburg.

An estimated 70 prisoners died during the forced march, according to the federal government. Some who survived likely ended up on the Thielbek and the Cap Arcona.

Germany began to collapse in April. Hitler committed suicide in April 1945, signaling the sure end of the war.

"In April 1945," according to stipulated testimony in Berger's case, "Mr. Berger and others fled into the woods and were coaxed to surrender."

The British Army took him prisoner. They held him until Christmas Eve, 1945.

"He was subsequently employed by the British as a truck driver into 1946," stipulated testimony states. "The British did not charge Mr. Berger or contact him as a potential witness during their war crimes investigation of Neuengamme subcamp personnel."

He moved to Canada with a wife and daughter in 1956 and then arrived in the United States in July 1959.

"Mr. Berger regularly renewed his permanent resident immigration status without incident," according to records. "He has had no adverse encounters with the law. He was regularly employed and retired to Oak Ridge, Tennessee."

Rosenbaum said he didn't know what profession Berger took up. He was trained as a machinist, records state.

Rosenbaum noted the 75th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day, or "V-E" Day, is coming up in May. After so many years, it's likely most if not all of those who came to the United States after working in the German camps are now dead.

Rosenbaum expects Berger's native country will take him back if he fails to win his appeal. He draws a German pension.

"Germany would not stand in the way of his return," Rosenbaum said.