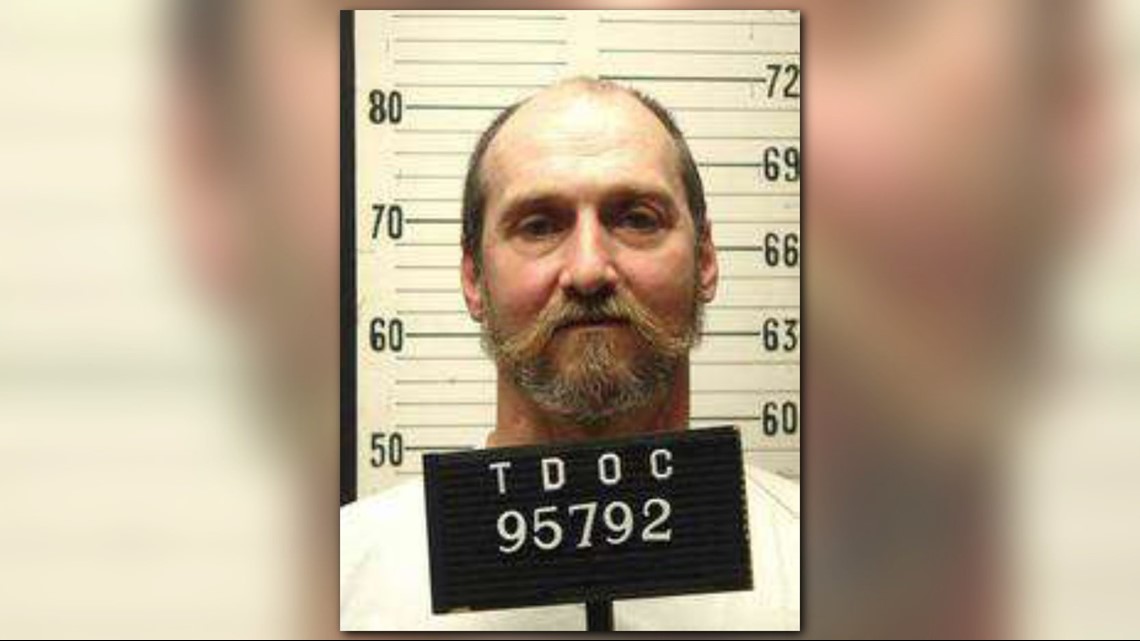

NASHVILLE — Death row inmate Edmund Zagorski died 7:26 p.m. CDT Thursday after Tennessee prison officials electrocuted him with the electric chair. He was 63.

He is the 134th person put to death by Tennessee since 1916 and the second person this year after Billy Ray Irick’s execution by lethal injection on Aug. 9. He is the first person to die by electric chair since Daryl Horton's execution in 2007.

Lt. Governor Randy McNally made the following statement on the execution:

"The ultimate penalty is reserved for the most heinous of crimes. This individual shot John Dale Dotson and Jimmy Porter and slit their throats in commission of a robbery. This individual then attempted to kill police officers to avoid being brought to justice. While there is little pleasure in it, there is no doubt justice was served tonight. I can only hope the families of the victims can now have peace."

Zagorski was convicted in the April 1983 murders of John Dale Dotson, of Hickman County, and Jimmy Porter, of Dickson. Prosecutors argued Zagorski lured them into the woods in Robertson County with the promise to sell them marijuana, and then he shot them, slit their throats and stole their money.

Two minutes before it was set to begin at 7 p.m., the U.S. Supreme Court denied Zagorski's appeal on the grounds of the unconstitutionality of choosing between the electric chair and lethal injection.

As dark clouds loomed over Riverbend Maximum Security Institution and the sunset changed the sky from bright pink to black, a police-escorted van arrived.

Eight people believed to be family members of the victims entered the prison to witness the execution.

They waited in front of a covered large window that looked into the execution chamber where on the other side of the glass Zagorski sat pinned in the electric chair, held down by buckles and straps with electrodes fastened to his feet.

The blinds opened for the rest of the witnesses to see Zagorski dressed in his cotton clothes, smiling and grimacing to the group.

He sat in the wired chair as prison staff placed a wet sponge that had been soaked in saline solution, and metal helmet on his freshly shaved head. He continued smiling, but would grimace each time drops ran down his face.

Zagorski raised his eyebrows, appearing to be communicating to his attorney. She sat while nodding and tapping her heart, looking at Zagorski.

“I told him, when I put my hand over my heart, that was me holding him in my heart,” Zagorski’s attorney Kelley Henry told The Tennessean. She said Zagorski smiled, to encourage her to smile back.

Then his face was covered with a black shroud so the witnesses couldn't see his face as electricity jolted through his body.

The warden gave the signal to proceed. Zagorski lifted his right hand several times in what looked like attempts of a wave, before he clenched his hands into a fist as the first charge of 1,750 volts of electricity through his body for 20 seconds.

Henry said both pinkies appear to either be dislocated or broken due to the force as he pulled against the straps. She also said there were signs that Zagorski was breathing during a short pause before the second jolt was administered for 15 seconds.

The doctor overseeing the death appeared in view to check on Zagorski.

Zagorski was dead. The blinds into the chamber closed.

Ten minutes later, the victims' families exited the building and drove away in the van without speaking publicly.

"First of all I want to make it very clear I have no hard feelings. I don’t want any of you to have this on your conscience, you are all doing your job, and I’m good," Zagorski said before he was taken from his cell to the execution chamber, according to Henry.

"It was very important to him that this not be a day of sadness for us," she said. "He very much wanted a light mood, and he was in a light mood every time I saw him."

Zagorski’s death comes after last-minute legal wrangling.

Zagorski was set to die three weeks ago.

His request to die by electric chair saved his life — at least for a few weeks, when Gov. Bill Haslam granted reprieve three hours before his scheduled execution on Oct. 11.

The move bought the state time to prep the chair during last-minute legal wrangling.

Zagorski requested death by electric chair with hope that death would come instantaneously — the “lesser of two evils” compared to lethal injection, argued federal public defender Kelley Henry.

According to a doctor who reviewed Irick’s execution, Irick felt searing pain akin to torture before his death. Experts argue that inmates experience the feeling of “drowning and burning alive at the same time” that reportedly comes with lethal injection.

Questions of if and how Zagorski’s death would play out continued to swirl up over the past month.

During his 1984 murder trial, the then-28-year-old Zagorski told his defense team he wanted the death penalty and forbid them to contact his family or dig into his past, according to documents from the Tennessee Supreme Court.

But once on death row, Zagorski changed this mind. Thirty-four years and 22 appeals later, he and his new defense team fought for a last-minute court decision to save his life, claiming his trial attorneys made errors in representing him

On Oct. 10, the U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals issued a stay. The state responded the next morning and asked the U.S. Supreme Court to deny a stay and allow the execution to move forward.

Zagorski had asked the federal court to to force the state to use the electric chair for his execution — the state initially refused and planned to move forward with lethal injection but District Judge Aleta Trauger ruled that afternoon that the state could not use lethal injection until Zagorski's claim had been heard.

Trauger's ruling likely triggered Haslam’s move for reprieve.

An unheard childhood

Zagorski grew up poor in Tecumseh, Michigan, about an hour southwest of Detroit, according to an appeal filed to the Tennessee Supreme Court in 1998.

His father played little role in his life, and his mother, impaired by a brain injury, had wanted a daughter, according to the appeal.

He could not read or write between the ages of 8 and 10. He developed a stutter.

He had no eye glasses for a time, despite having poor vision.

At an early age, he was exposed to drugs and alcohol.

Zagorski had “minor skirmishes with the law as a juvenile and federal drug convictions as an adult,” the appeals documents show, but had no convictions for violent crime before the murders of John Dale Dotson and Jimmy Porter in April, 1983.

If the jurors had known this, Zagorski and his team argued, it would have kept him from the death penalty.

A 'calculated' murder

On April 23, Dotson was making plans with his friend Porter to meet a man he knew as Jesse Lee Hardin to buy 100 pounds of marijuana.

Posing as Hardin, Zagorski told Dotson he’d worked as a mercenary in South America and worked a stint drilling for oil near New Orleans.

Though not more than acquaintances, the men agreed to meet Zagorski and authorities later found their bodies in a secluded, wooded area near Interstate 65 in Robertson County.

When her husband didn’t return home after the meeting, Marsha Dotson said she knew immediately something had happened. Although search efforts began right away, the bodies of Porter and Dotson weren't found for about two weeks.

There was a national manhunt for Zagorski. He was eventually spotted in Ohio and was apprehended after a shootout with police.

The inmate’s statements about his time in South America could never be verified, according to Sumner County District Attorney Ray Whitley, who was an assistant district attorney in 1984 who tried the case and sought the death penalty.

“Whether he was or not, who knows,” the prosecutor said. “He was apparently a very convincing person to make friends and get these people to believe enough to go out into the woods with him.”

SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM: The most thorough coverage starting from the moment news breaks

A fight for a 'rehabilitated man'

In the 1984 trial, life without parole not an option. It's a point Zargorski's attorney Robert Hutton pushed in the petition to commute his sentence.

The jury did not have the option to sentence him to life without parole because their only options in the 1984 trial were death or the life with the possibility of parole.

Six of the surviving jurors in the case agreed life without parole was an appropriate sentence for Zagorski, the clemency request stated. Today, a death sentence would not be given if just one juror wanted life without parole

And while Marsha Dotson for more than 30 years wanted nothing more than to see Zagorski put to death for his crimes, she has since "softened."

“I’ve come to realize that it’s not my place to condemn somebody, to let them die. I can’t play God," Dotson said.

Hutton also argued Zaroski has also shown "exemplary" behavior during his prison term as a "rehabilitated man." He never received a single disciplinary infraction and testimonies from officers and volunteers detail his trustworthy, hardworking, respectful and peacekeeping demeanor.

"His extraordinary rehabilitation demonstrates that if you commute Ed's sentence, he will continue to make the prison community a safer place for both officers and inmates," Hutton wrote in the petition.

The Roman Catholic bishops of the Nashville and Knoxville dioceses have also spoken out ahead of Zagorski's execution.

What's next for executions in Tennessee?

The debate of capital punishment has burned hot in Tennessee. Like many states, Tennessee’s death penalty law was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972.

Officials moved quickly to pass new laws governing the punishment in 1975. But legal challenges kept the death penalty on hold, and it wasn’t until 2000 that an execution was carried out.

Six men were put to death by lethal injection and one was executed by electric chair through 2009. A hiatus followed until Irick's execution on Aug. 9.

Irick and Zagorski were part of a group of 32 death row offenders suing the state over its lethal injection method. The Tennessee Supreme Court ruled in a 4-1 majority in October the drugs can continue in Tennessee even though medical experts said the state's controversial three-drug protocol tortures inmates to death.

The state in the past has also gone back and forth on whether the electric chair should be used again. It's unclear how Zagorski's request for the chair will impact executions in the state moving forward but expert on executions predicts more death row inmates could follow his lead.

Death row inmate David Earl Miller is set to be executed in early December.

Miller, 61, was convicted of killing a disabled woman in South Knoxville with a fire poker in 1981. He is the longest current member of Tennessee's death row.

Includes reporting by reporter Natalie Allison.