The attacks that killed eight people at three spas in or around Atlanta in mid-March helped further ignite a nationwide movement to not only stop hate against the Asian American Pacific Islander community but raise awareness about decades of unfair and blatantly racist acts.

Six of the victims from the spa shootings were of Asian descent. While the pandemic and anti-Asian rhetoric helped fuel numerous assaults, harassment and discrimination since March of last year, the killings have become the latest tragedy in more than 150 years of racist and violent history in the country.

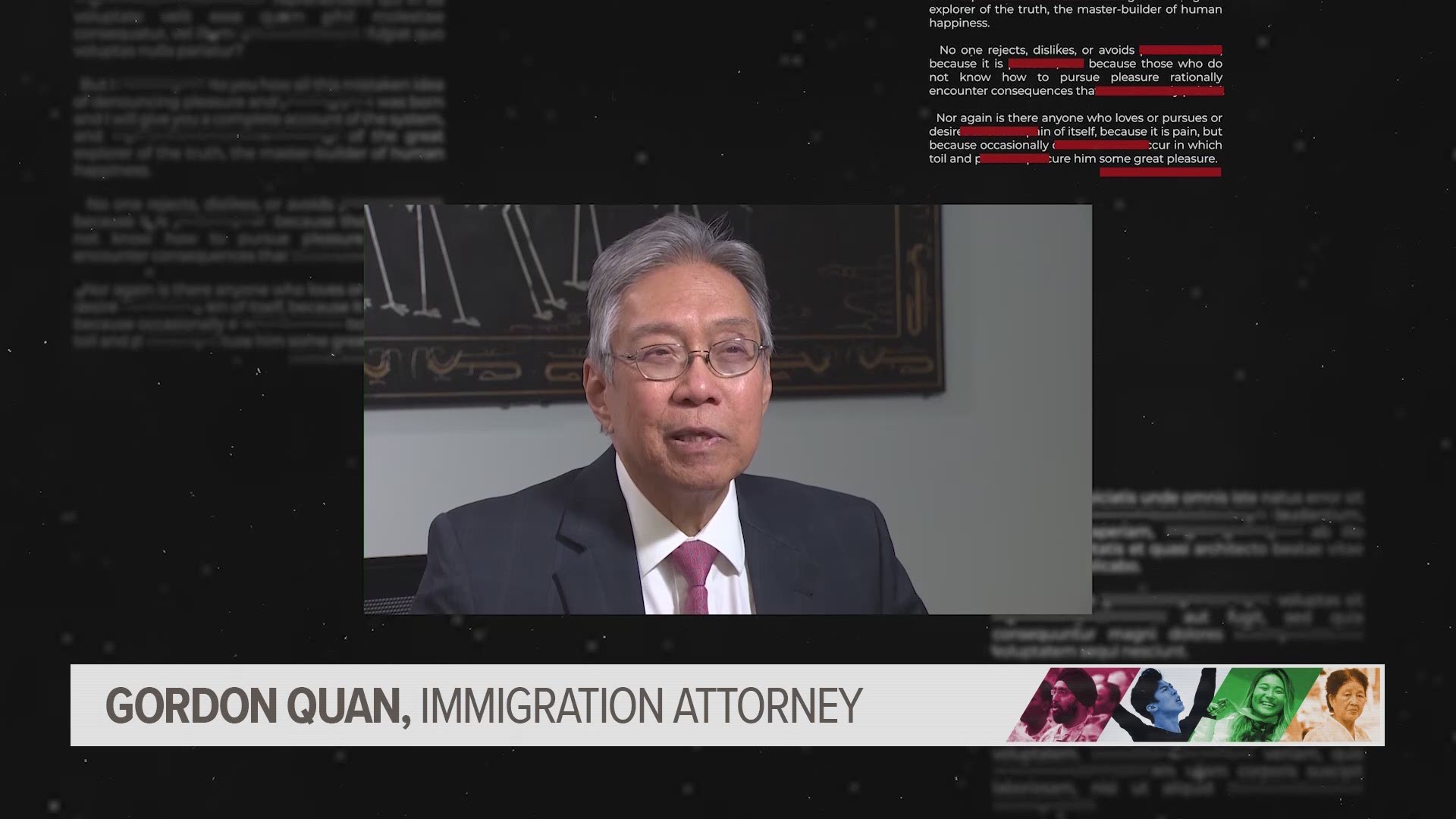

To understand the struggle to adapt in the U.S., look no further than Gordon Quan, a leading immigration attorney based in Houston, Texas. The American journey for his family began when his grandfather, a successful businessman in China, fled after being targeted by emerging communists in the early 1900s.

A warrant was issued for his arrest because he was considered a capitalist. His exodus took him to Mexico and eventually the U.S., where in San Antonio Chinese residents were not permitted to buy a home. The Quans moved to Houston, where they opened a grocery store which had quarters behind it.

“I look with great pride, the courage my grandfather had coming to America,” Quan said.

The journey helped turn a young Gordon Quan into a nationally recognized immigration attorney. He knows better than most how hard ‘crossing to America’ has been for many groups. For Asian Americans, it was marked by the country’s first immigration ban based on race in the 1800s.

It stems as far back as the Page Act of 1875, a restrictive federal immigration law that targeted Chinese women from entering the country.

The more recognizable Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 soon followed, which largely stopped Chinese men from immigrating and prevented those already in the U.S. from becoming naturalized citizens. States in the West pushed the law through by cutting a deal with states in the South that targeted another minority.

“The people of the South didn't care about the Chinese,” Quan explained. “There weren’t any Chinese there."

Quan said government officials in the South cared more about the Jim Crow Act and the number of African Americans being elected to Congress at the time.

Meanwhile, Chinese workers who made the trek to the West to work on the railroads were subsequently discharged. One of the major occupations they were able to engage in was mining. Due to economic circumstances, they were viewed as competitors for work and therefore, seen with a great deal of hatred by white immigrant workers and were subjected to ethnic cleansing.

Three years later, in 1885, an ongoing dispute over Chinese coal miners in Wyoming would become a bloodshed when they refused to join a strike for higher wages. In return, a mob of white coal miners attacked in what has become known as the Rock Springs Massacre.

The mob killed 28 Chinese miners, injured others and burned dozens of homes. In what was referred to as their Chinatown, members were driven out of their homes.

“White immigrant workers thought they were going to be displaced by these Chinese workers and decided to engage in vigilante justice,” University of Colorado at Boulder professor William Wei said. “They took matters into their hands and decided to arm themselves and drive them out of the community.”

Tension between cultures went beyond borders, like when the U.S. colonized the Philippines after winning the Spanish-American War in 1898. It took $20 million paid to Spain to seal the deal. Filipinos tried to fight for independence in what they called a revolution, but the U.S. government called it an insurrection.

Military officials uprooted indigenous tribesmen to showcase them at the 1904 World's Fair in Saint Louis.

“Filipinos were displayed in this world's fair as savages, as barbarians, almost like animals,” Jonathan Melegrito, former director of the National Federation of Filipino American Associations, said. “America was justifying going to the Philippines to civilize and Christianize the Filipinos.”

Young Filipinos eventually became farmers in California, but under cheap pay and poor living conditions. In January 1930, a white mob attacked Filipino farmworkers for dancing with white women in Watsonville, California. That sparked similar attacks in other cities in Northern California.

“They [mobs] would create riots, assault Filipinos and they would attack and stalk them,” Melegrito added.

By World War II, China and the U.S. became allies in the fight against Japan. The legendary air unit, The Flying Tigers, was a high-profile example. The group initially had 311 members who were tasked with protecting China from Japanese military. While it lasted for only a year, the Flying Tigers destroyed 297 enemy aircraft at a ratio of 20-to-1.

Staff Sergeant Lewis Woo Yee, then an 18-year-old soldier, helped with the petition that ended the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. At 95-years-old, Yee was eventually awarded a congressional gold medal.

“When you wear the uniform to serve your country, they pay attention to us, so in 1943, they did away with it,” Yee said.

However, WWII also brought out an uglier side to the country when 120,000 Japanese residents in the country, 70,000 of them U.S. citizens, were sent to internment camps for the duration of the war. Anti-Japanese worries, rooted by the war and fear, prompted the government to implement a severely drastic policy.

Meanwhile, about 33,000 Japanese served in the U.S. military and helped comprise the legendary 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The unit was the most highly decorated unit of the entire war.

Decades later, the Vietnam War sent 130,000 refugees to the U.S. after the fall of Saigon. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, many became shrimpers on the Gulf Coast. However, the competition triggered shootings, boat burnings along with assaults and intimidation by the Ku Klux Klan.

The shrimpers were terrorized despite seeking out a better life, but a Southern Poverty Law Center lawsuit helped put a stop to the threats and destruction.

In 1982, the murder of 27-year-old Vincent Chin outraged and galvanized the Asian American community. Chin was killed the night of his bachelor party in Detroit. Two white Chrysler autoworkers, Ronald Ebens and his 22-year-old stepson Michael Nitz, beat Chin to death with a baseball bat following an argument.

They were heard shouting racial slurs and saying, “It’s because of you little motherf*****s that we’re out of work.”

Chin was confused for being Japanese when he was in fact Chinese. In trial, the men received a $3,000 fine but zero prison time. The case has often been attributed as a pivotal point for Asian American activism and civil rights engagement.

By Sept. 11, 2001, as the world was grieving, the terrors attack also spawned even more hate, this time toward South Asians and people of Arab, Muslim and Middle Eastern descent. Bullying, harassment, racial profiling and vandalism at places of worship became a dark outcome. Fears following the attacks turned into blame against the community.

The first month after Sept. 11, there were more than 300 cases of violence and discrimination against Sikh Americans alone in the U.S. Nearly 20 years later, tracking hate crimes against the community continues to this day.