KNOXVILLE, Tennessee — The way Randy Boyd sees it, a proposed downtown stadium would be much more than the home of his Double A baseball team.

The millionaire entrepreneur and philanthropist believes it can be "The People's Park," a place for walkers, shoppers, sports fans, craftsmen, music lovers, even couples who want to say, "I do."

"I think this could be such a catalytic event for all of East Knoxville and downtown. The idea of building a baseball park is not something of creating a venue just for baseball, but creating an entire entertainment venue that can have concerts, soccer, all kinds of other tournaments, family reunions, we could have farmers markets. But it'll be a park that's used year-round for multiple uses," he told 10News during a recent site tour.

"So it's not really just about baseball. It'd be an opportunity to bring the community together for a lot of different events and have a seismic economic impact on the community.”

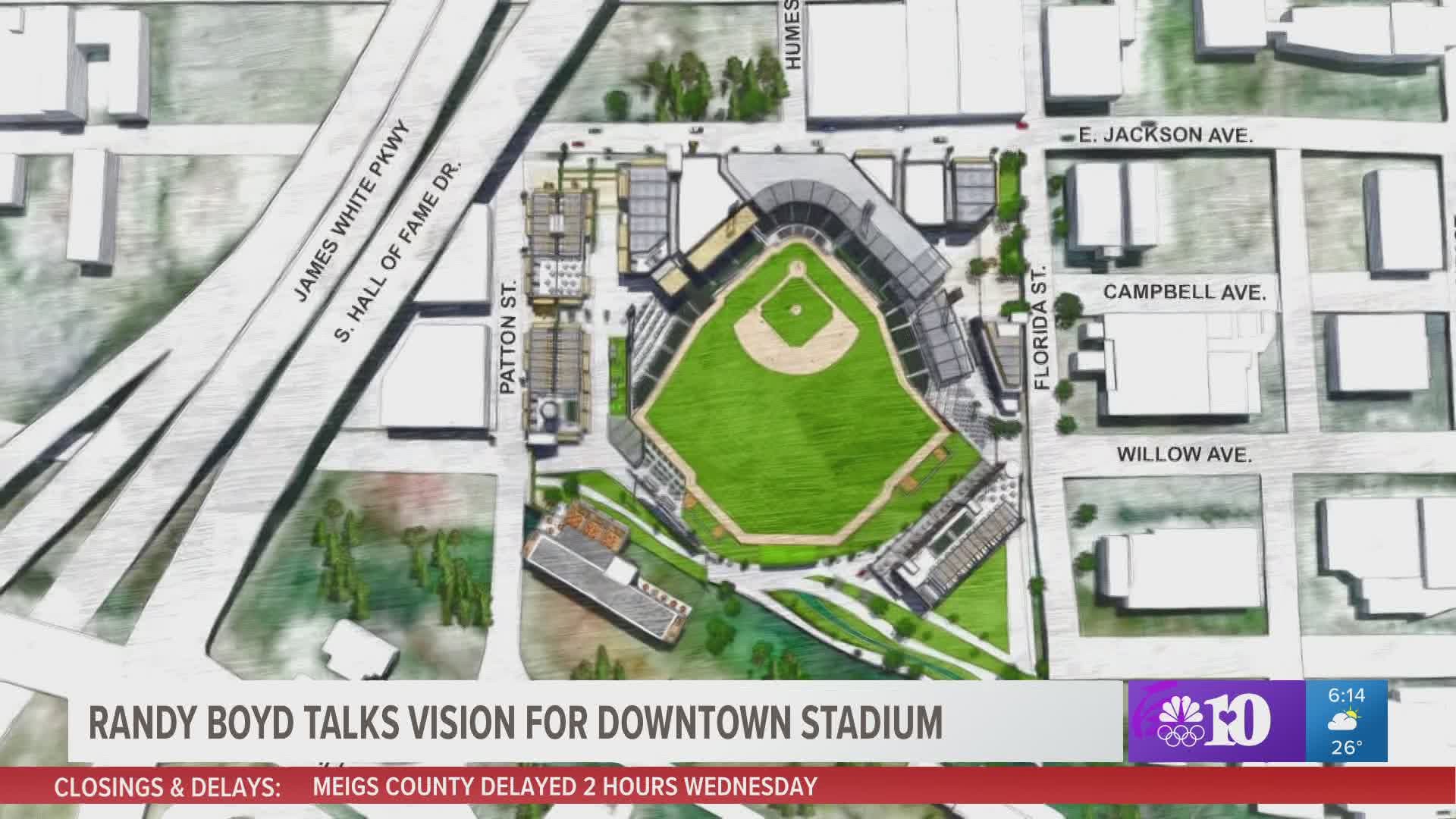

Right now, demolition crews from Denark Construction are tearing down the old Lay's packing plant on Jackson Avenue below the James White Parkway.

Including the plant site, Boyd owns about 12 acres down there, most of which he's proposing to hand over for a publicly built stadium. In addition, he's planning to build surrounding apartments, retail shops and restaurants.

The South Knoxville native, the former head of Tennessee economic development under Gov. Bill Haslam, has assembled a group of investors for the $140 million commercial and residential part of the project.

His Tennessee Smokies, which now play in Sevier County, could start playing in the estimated $65 million park as soon as spring 2023, if all planning goes as envisioned. They'd play 70 home games a season downtown.

“We plan on having the stadium open 365 days out of the year, so that people who want to come and walk the concourse can use it," Boyd said.

City and county staff have touted the park as a place that'll be in use at least 200 times a year. But Boyd told Knoxville City Council members and Knox County Commission members earlier this month he actually thinks the center could host some 350 events a year.

A WALK AROUND THE PARK

Boyd already sees how the project will be laid out.

He led WBIR on a site tour recently, pointing out spots such as the future stadium entrance, home plate, a spot for a public plaza that could host farmers markets and restaurants and shops.

"Where we are sitting now would be a prime piece of real estate for somebody to have a retail shop from the first floor. And then above it will be the apartments," he said.

Some 7,000 seats are envisioned inside the complex. But Boyd wants people to mingle, to wander, to explore.

“We've got a lot of enthusiasm. We've got a lot of plans. But we still got a lot of work left to do," he said.

That work includes convincing the City Council and County Commission that it's a project worth doing. Last week, the two governing bodies met for the first time together to hear how it would all come together.

The next six months -- preparing the financing, blessing the building plans -- are key. As envisioned, construction could start in the fall and continue through early 2023.

It's an ambitious schedule.

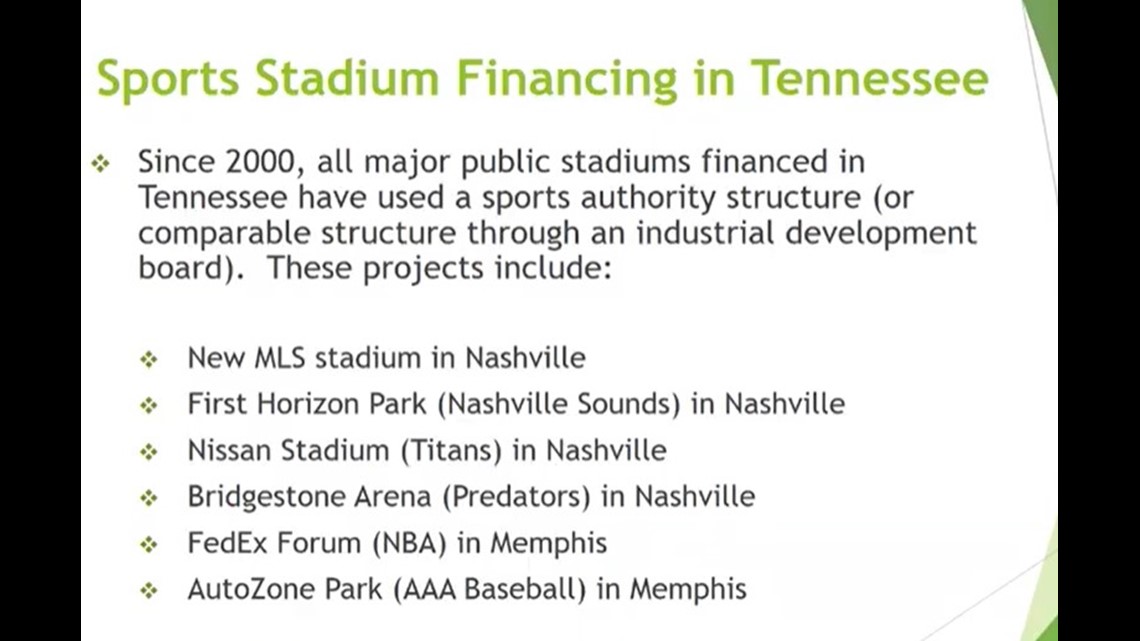

A newly created sports authority -- which still needs appointees -- would issue bonds for construction. The debt would be paid back over 25 or 30 years from a variety of sources including team rent, sales taxes from concessions and sales taxes collected from commercial development within a defined neighborhood boundary.

Council and County Commission have approved creation of the sports authority. But they've got to bless the people who will sit on it and oversee stadium planning and financing.

Most elected officials sounded engaged and enthusiastic during a Feb. 4 workshop session. But they also had plenty of questions.

There's also that lingering question that comes up with all publicly funded stadiums in America: How does it help anyone but the team owner himself?

Knoxville Vice Mayor Gwen McKenzie represents the 6th District in which the project will reside.

McKenzie wants to know: What commitments will be made specifically to East Knoxville to ensure the stadium is a success? How will her constituents benefit?

"I can see advantages. And I can also see some potential things that could not be an advantage. But again, the jury's still out on that and I'm looking forward to just getting more information,” she said.

City and county staff say the project would tie together downtown, the Old City and East Knoxville, including nearby schools and the Austin Homes housing development.

But Boyd, the president of the University of Tennessee System, is thinking of impacts far beyond bricks and mortar.

He sees opportunities for people to learn skills beyond working at a ballpark.

He sees the potential for workforce development, the recruitment of the local labor force and partnerships with neighborhood schools such as Vine Middle and Green Magnet Academy.

FROM EYESORE TO SHOWCASE

At a minimum, Boyd believes his development plans will bring new life to a part of town that's been decaying and overlooked for decades.

The old Lays plant has been closed for years.

The area immediately east of the James White Parkway near Jackson and Willow avenues is primarily industrial with little human traffic. These days the events that tend to draw the most people down there are music festivals under the parkway and 5K races, when hundreds of people run up and down the streets and through the Old City.

It can be much different, Boyd said. Professional baseball, which left Knoxville in 1999, can come back to a new home just a few blocks from where it once was played at Bill Meyer Stadium north of Magnolia Avenue.

The neighborhood can be a place to live, work and shop. The stadium could be a place where people go on their lunch hour or to get a morning walk in before heading to work.

"Ten years from now, just imagine: All this industrial waste turns into this magnificent part of our city," Boyd said.