PALL MALL, Tenn. — High atop a hill in Fentress County’s Wolf River Valley, a small stone schoolhouse stands as a testament to an East Tennessee hero and his own life’s work.

Sergeant Alvin C. York was born in the valley in the late 1800s, working as a farmer and blacksmith before being drafted for World War I in 1917. He was an objector as part of the Church of Christ and Christian Union and claimed exemption based on religious beliefs.

“He doesn’t want to kill. He doesn’t believe in violence of any kind,” said Nate Dodson, park manager of the Sgt. Alvin C. York State Historic Park.

FULL SERIES: Explore Tennessee's Abandoned Places

His exemption was denied, and York was sent overseas. In 1918, he and a group of seven men found themselves behind enemy lines in France. They captured 132 German soldiers and marched them back to the American line, earning Congressional Medals of Honor.

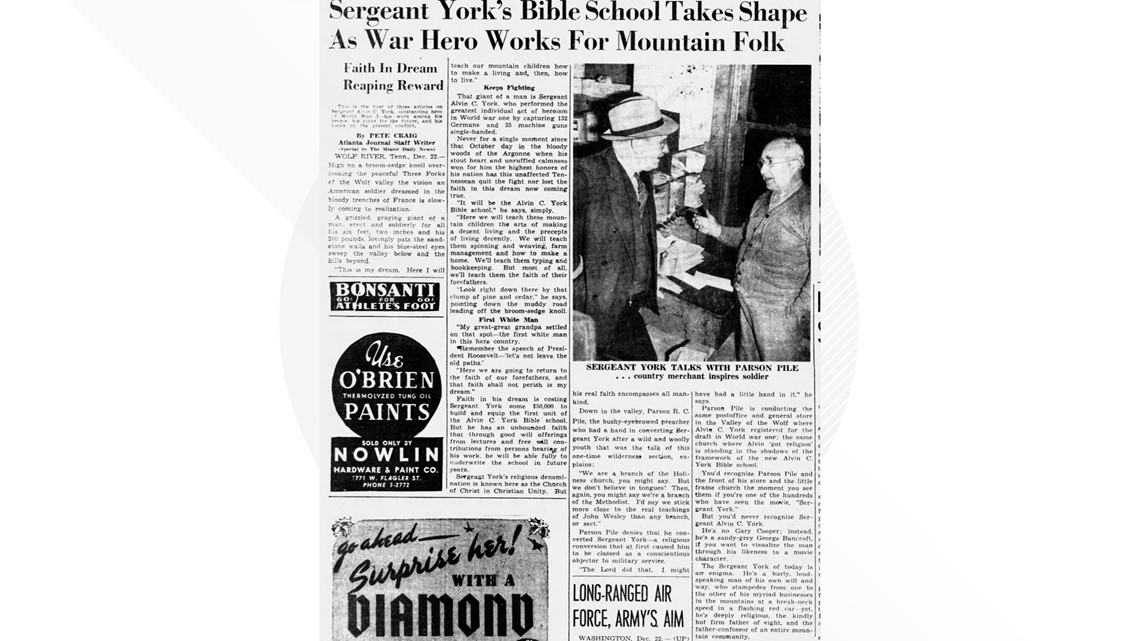

“He returns this conquering hero. Everyone knows his name. He's famous across the nation, and he sort of attempts to go back to his old life,” Dodson said. “He's now famous. That's not going to happen for him so he focuses really the rest of his life on providing education to the valley here, to the county that he lived in.”

His time abroad showed him the need for educational opportunities back home so he built two schools: the York Institute in Jamestown and the York Bible School in Pall Mall.

“[The Bible school] represents his story better than most simply because it's tied to his time in the service,” Dodson said.

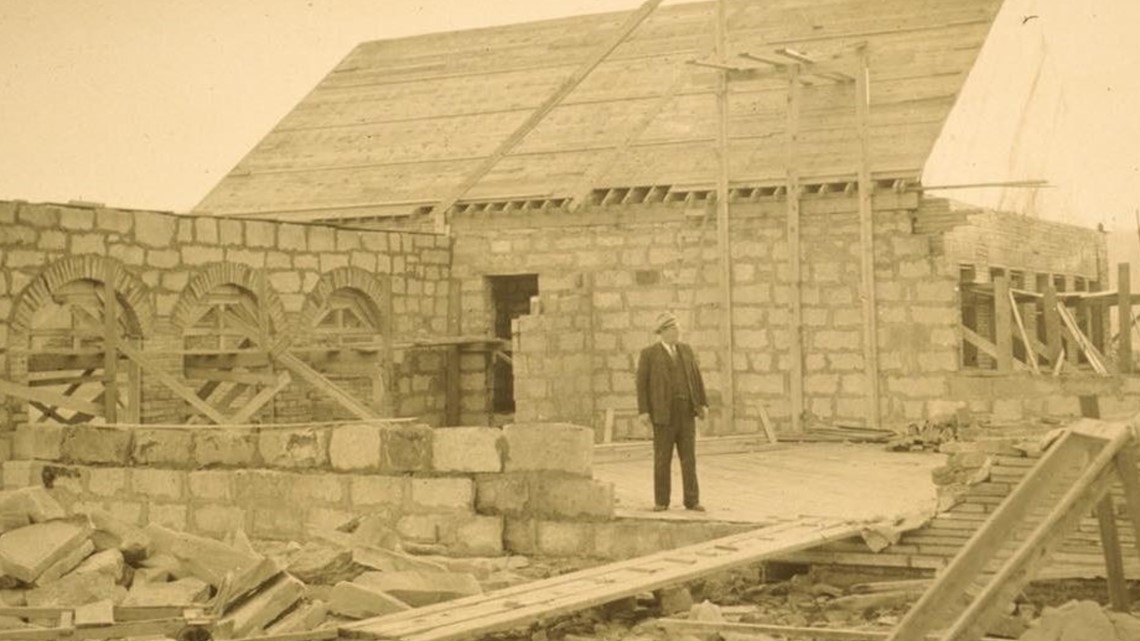

While working as a supervisor at a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp in Crossville, York used his fame to fund the Bible school. Proceeds from the 1941 movie about his life, “Sergeant York,” went to construction.

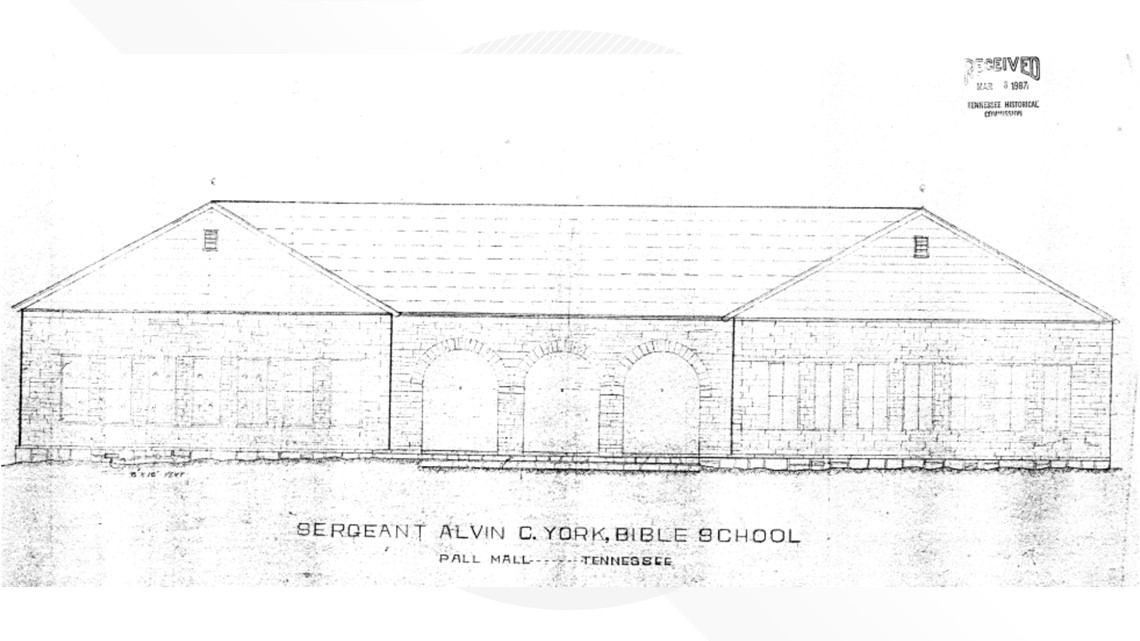

York tapped O.P. Pile, who was working with him at the CCC camp, to design the building, and he made an agreement with a Wolf River Valley resident named Grover Crouch to build it.

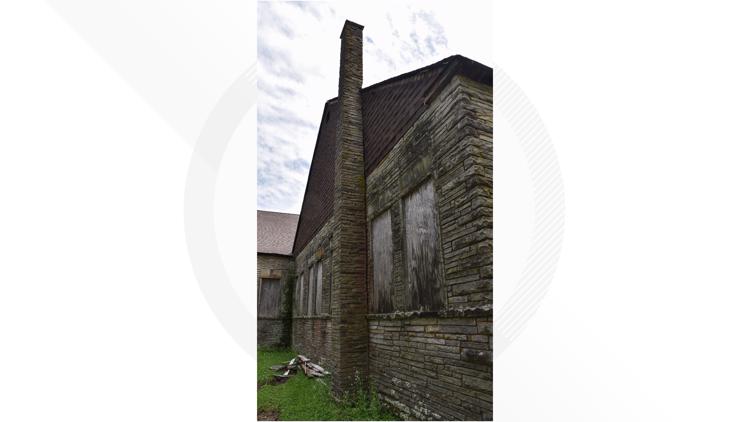

The school was made out of Crab Orchard stone, a type of sandstone from the Crab Orchard Mountain of the Cumberland Plateau, with enough room for two classrooms, an office and an auditorium. The arches over the entrance resembled other CCC projects from the time.

“We have letters and newspaper articles where he talks about this building. It was honestly a struggle for him to get it built here. He talks about some of the experiences he had in the war were easier than some of the struggles that he faces when he gets home,” Dodson said.

The York Bible School opened around 1944 and started holding summer classes.

“He saw it as a religious institution that would also teach trades to his local community members. These are folks that may not have gone to school at all, and they could learn a trade, a skill to better their life with,” Dodson said.

Students filed in for lessons through the 1950s, but attendance waned with York’s failing health after a stroke in 1954.

“He's the driving force behind the school. It doesn't really see the attendance that he wanted to see,” Dodson said.

Classes stayed in session until 1964 when York died, and the Bible school was left behind.

York’s wife, Gracie Williams, sold the home site in the valley to the State of Tennessee in 1974, which became the Sgt. Alvin C. York State Historic Park.

Even under state ownership, trees grew around the little stone schoolhouse, practically swallowing up the hilltop. Its secluded perch spared the school from most break-ins, but Mother Nature still found a way to leave a mark.

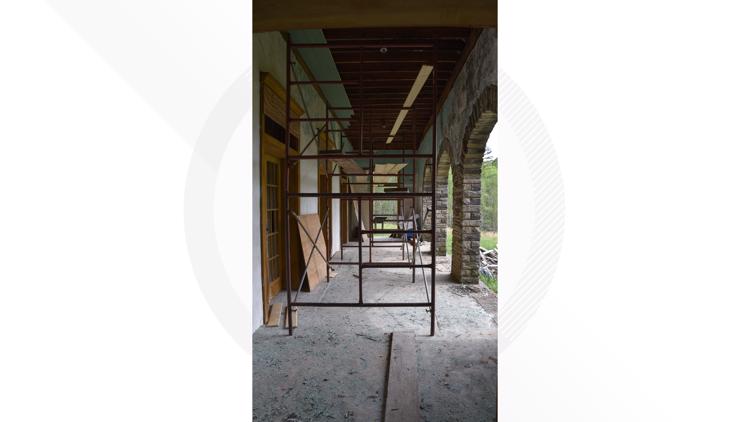

Buzzards roosting on the roof ripped up shingles. Rain rotted portions of the wooden floors. Windows broke. Blue-green paint on the walls chipped. Metal fixtures rusted.

“It probably looked really abandoned back then. You’d be in the woods and come across this building surrounded by trees,” Dodson said.

Abandoned Places: York Bible School

After being lost in the woods for decades, the York Bible School was brought back into the light when rangers began removing trees from the hillside a few years ago.

When the COVID-19 pandemic drove more people to outdoor spaces, the state park saw an uptick in visitors, which allowed them to apply for a grant.

“My mind immediately went to the Bible school,” Dodson said. “We applied for just a small grant to preserve the school in such a way that we can seal out any more damage. Any existing damage that’s there, we can start addressing that.”

Dodson said the building’s remote location in the park put other projects, like restoring the York home, ahead of it for years.

“While its location sort of was prohibitive to it being restored, I think it adds to its charm too,” he said. “You’re in this beautiful stone building up on this hill with an overlook above the valley.”

Contractors have already started fixing the leaking roof and soil erosion around the foundation with plans to replace the gutters, repaint the front porch ceiling and restore the windows. With the restoration underway, the park already has ideas for the schoolhouse.

“One of the ideas we really like is as a folklife center, a place where you can learn trades, you can have people come and demonstrate lost art skills, you can have music, you can have events here, those kinds of things,” Dodson said. “We've thought about housing archives. We have a pretty extensive York family archive collection so that's a possibility for the space.”

Though the work has just started on the stone structure, the York Bible School could once again serve as a place of learning in the Wolf River Valley.

The park hosts regular events and driving tours throughout the year for visitors. More information is available on its website.

Reporter’s note: Though many of these buildings are unused and empty, they sit on private property that is still actively used in some cases. Do NOT attempt to unlawfully enter any of these places without permission. Many of them are structurally unsound and pose potential health hazards, like asbestos and lead paint. WBIR contacted all owners and obtained permission prior to visiting.

For more stories from East Tennessee's Abandoned Places, check out our YouTube playlist: