Emily Snook is the daughter of a Southern Baptist pastor. She met her husband, also a pastor, while they attended a Southern Baptist university

Yet the 39-year-old Oklahoma woman now finds herself wondering if it’s time to leave the nation's largest Protestant denomination, in part because of practices and attitudes that limit women’s roles.

“Every day I ask that,” Snook said. “I don’t know what the right answer is.”

She’s not alone. Among the millions of women belonging to churches of the Southern Baptist Convention, there are many who have questioned the faith’s gender-role doctrine and more recently urged a stronger response to disclosures of sexual abuse perpetrated by SBC clergy.

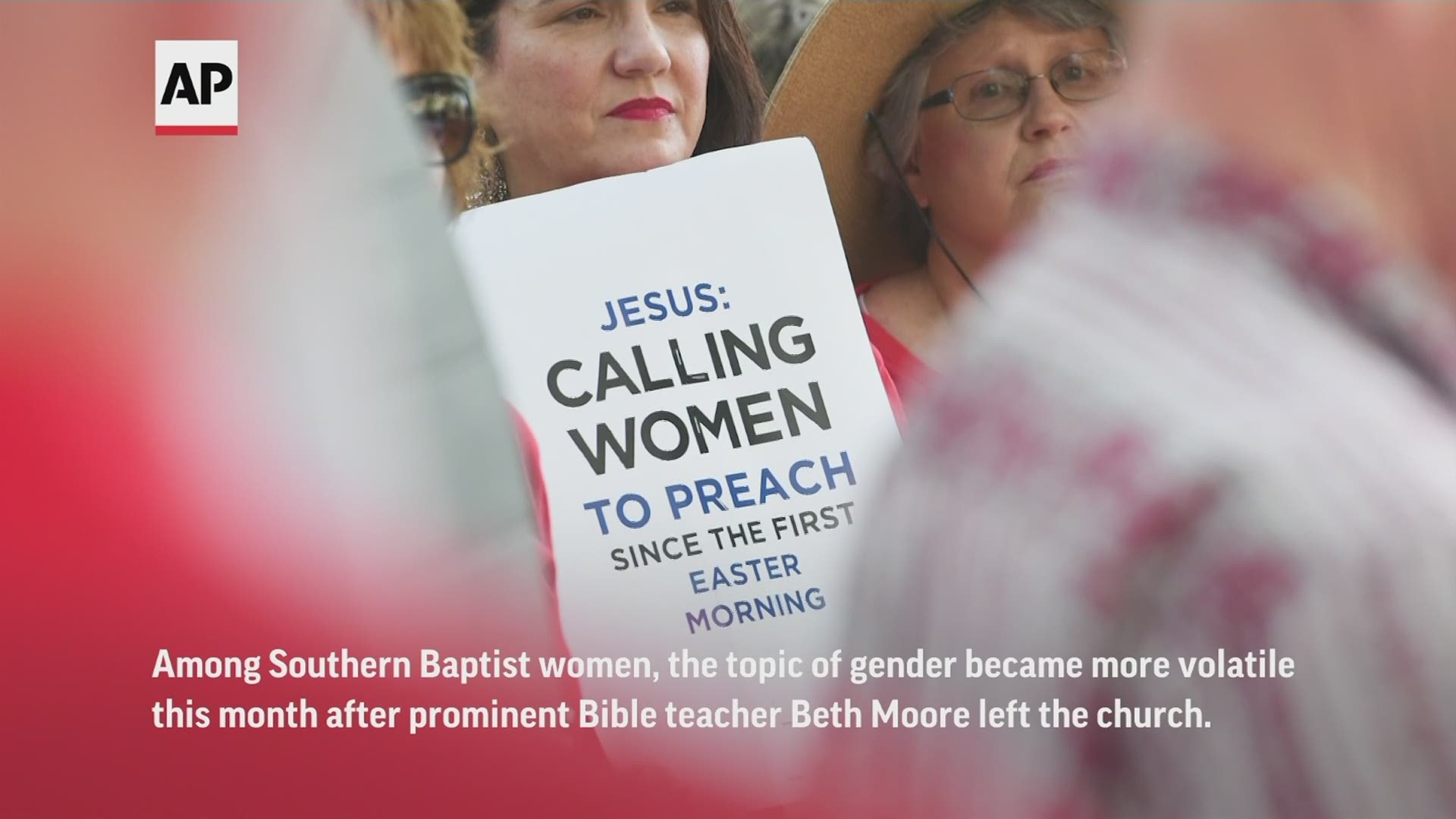

For many SBC women, even those committed to staying, the topic of gender became more volatile this month when popular Bible teacher Beth Moore said she no longer considered herself Southern Baptist. Moore, perhaps the best-known evangelical woman in the world, had drawn the ire of some SBC conservatives for speaking out against Donald Trump in 2016 and suggesting the denomination had problems with sexism.

Karen Swallow Prior, a professor of English and Christianity and Culture at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, has belonged to an SBC megachurch and wrote a passionate article in February explaining why she remains Southern Baptist.

Yet she is among a number of SBC women publicly sharing their dismay about sex abuse and the vitriol directed at Moore.

“Beth has been scorned, mocked, and slandered while doing exactly what the denomination has determined she could and should do: be a woman teaching other women,” Prior said via email.

“I cannot count the number of women who have reached out to me over the past few years, lamenting and grieving the way women have been and are being treated in some SBC churches and by some denominational leaders,” Prior added. “If these women leave, it won’t be because Beth left. It will be because the men the Baptist Faith and Message says are supposed to lead in Christ-like ways have failed to do so.”

Prior was referring to the doctrine adopted by the SBC in 2000 which espouses male leadership in the home and the church and says a wife “is to submit herself graciously to the servant leadership of her husband.” It specifies that women cannot be pastors, citing the Apostle Paul’s biblical admonition, “I do not allow a woman to teach or to have authority over a man; instead, she is to remain quiet.”

Snook, who lives in Norman, Oklahoma, said she grew up being taught that men were leaders in the church and the home “to protect women, to lift them up.”

“Is it about protecting women — or is it really about protecting your power and covering up sexual abuse in the church?” she asked. “That’s caused a crisis of faith among a lot of women and men.”

Snook gained some attention — and criticism — in Southern Baptist circles when she posted an article in January on a blog called SBC Voices describing how she found herself admiring Vice President Kamala Harris despite her support for abortion rights. Now, Snook and others in her circle are pondering whether they have a future in the SBC.

“Do we stay and work for what we’re supposed be?” she asked. “If we all leave, are we abandoning our responsibility?"

Katie McCoy, a professor of theology in women’s studies in the undergraduate branch of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, tells her female students there are meaningful roles they can play in the SBC even if pastoring is off-limits. But she says many Southern Baptist women, including students of hers, were unsettled by the criticism of Moore.

“There are a lot of women who will never have the scope and reach of a Beth Moore but believed they had something to contribute because of her,” McCoy said. “It’s those women who look at the online vitriol and feel discouraged before they even begin, thinking, ‘If this is what they say about Beth Moore, what will they say about me?’”

Melissa Edgington, who is married to an SBC pastor in Olney, Texas, and describes herself as a stay-at-home mom of three children, says she’s had lifelong devotion to her denomination. She also has been an admirer of Moore.

“I have lost count of the number of times I have seen evangelical men on social media repeating that awful command ‘Go home’ to Beth Moore,” she said via email. “I wonder if they realize when they say those two words with such glee, they are sending a message to all women that our giftings and opinions and ideas may not be all that welcome in our denomination.”

Under certain circumstances, women can make professional strides in the SBC world — teaching at seminaries, working at SBC missionary organizations or, like Moore, carving out a niche as Bible teachers for a female clientele.

At First Baptist Dallas, the outspoken conservative pastor, Robert Jeffress, has encouraged daughter Julia Jeffress Sadler to be active in ministry, even though he cautioned her at age 11 that she couldn’t hold the title of pastor.

“He explained to me, Julia, you can’t be a head pastor for the same reason I can’t have babies. That’s not God’s design,” Sadler said.

Sadler, 33, directs a program at her father’s megachurch called Next Generation that develops ministries for teens, college students, single young adults and young moms. She says there are about 1,500 participants, with a 60%-40% female-male split.

“A lot of times we focus on the one thing that the Bible says women aren’t supposed to do, which is be the head pastor, instead of looking at all the things we can do,” she said. “We’re going to miss out in churches, miss out in ministries, miss out in Christianity as a whole, whenever we take women out of the equation.”

Sadler said her husband, Ryan, who oversees some of the church’s education programs, “understands that women are called to ministry, and that some of us really hate cooking. We have other things we’d like to do.”

Denise McClain Massey, who earned three graduate degrees from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, left the SBC after it formalized the no-women-pastors rule in 2000 and is now a professor of pastoral care and counseling at Mercer University School of Theology.

There are “painful, disorienting double-messages for women in the SBC,” she said. “You’re created in the image of God, but if you experience God leading you to be pastor, you get told there are limits to what you can do — sit down, go home, be quiet. There’s kind of a crisis where women feel shut down and dismissed and attacked.”

Christa Brown, a Colorado-based author and retired attorney who attended Southern Baptist churches from infancy until college and says she was sexually assaulted by a youth pastor as a teenager, has long been an outspoken critic of the SBC's response to revelations of sex abuse by clergy.

Brown sees a link between the abuse and the doctrine that women should submit to male leadership.

“It sets up interpersonal and institutional dynamics that help to foster abuse and cover-ups,” she said. “The SBC’s pervasive misogyny inculcates attitudes that, at best, are limiting of female potential, and at worst, are disrespectful and dehumanizing.”

She expects most Southern Baptist women will stay loyal to their churches but hopes others will “stop graciously submitting and start graciously walking.”

In some cases, entire congregations have walked away. Joel Bowman, pastor at Temple of Faith Baptist Church in Louisville, Kentucky, recently abandoned plans to move the congregation into the SBC fold. Bowman, who is African American, had differences with SBC leaders on racism issues and also gender roles — his wife, Nannette, is an associate minster at the church.

Towne View Baptist Church in Kennesaw, Georgia, is being expelled by the SBC for accepting LGBTQ people into its congregation. Its pastor, Jim Conrad, also opposes the SBC’s gender rules and is likely to affiliate with a Baptist denomination that allows female pastors.

“Tradition is fine,” said Cheryl McCree, a deacon at Towne View. “But when it comes to faith, we follow Christ. … We have to reach out to everybody.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through The Conversation U.S. The AP is solely responsible for this content.