This is a story that begins at the end -- the end of the life of Jessica Lyday -- and works its way backward. It's the story of how police, using the overdose victim's cellphone, tracked down the man who sold her a deadly hit of heroin.

On the morning of July 3, 2015, Lyday, 30, was found unresponsive in the bathtub of her mother’s West Knoxville home.

“As a mother, your world is never going to be the same,” said mother August Lyday of the death of her only daughter. “She was unique. At the same time, she was just as humble. She didn’t have a mean bone in her body. She just had a big ole heart.”

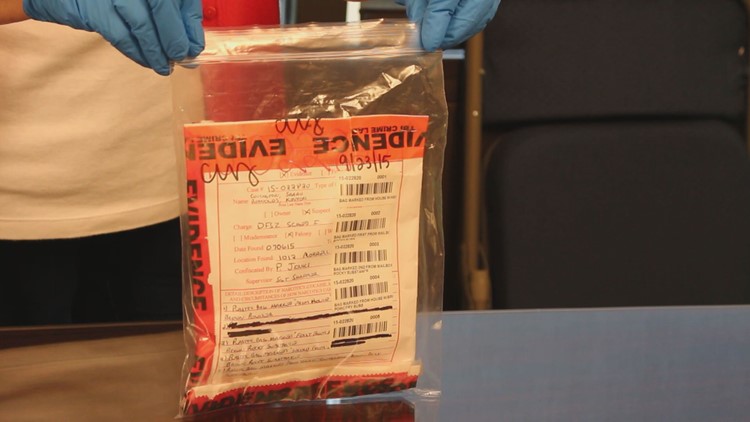

When Knoxville police investigators arrived at the home, one of the first pieces of evidence they used to begin their search for who sold her the drugs was Lyday’s cell phone. As they suspected, it held the answer about where the drugs came from.

“When someone overdoses and dies in our community, we want to know where they got those drugs. The way people communicate this day and age is with their cell phone,” said Charme Allen, the Knox County district attorney general. “That cell phone is a very valuable tool in finding out who our deceased victim was talking to prior to their overdose, and most likely that is going to be the person who supplied them with their drugs.”

Prosecutors in Knox County have focused in recent years on bringing homicide charges against drug dealers in connection with overdose deaths.

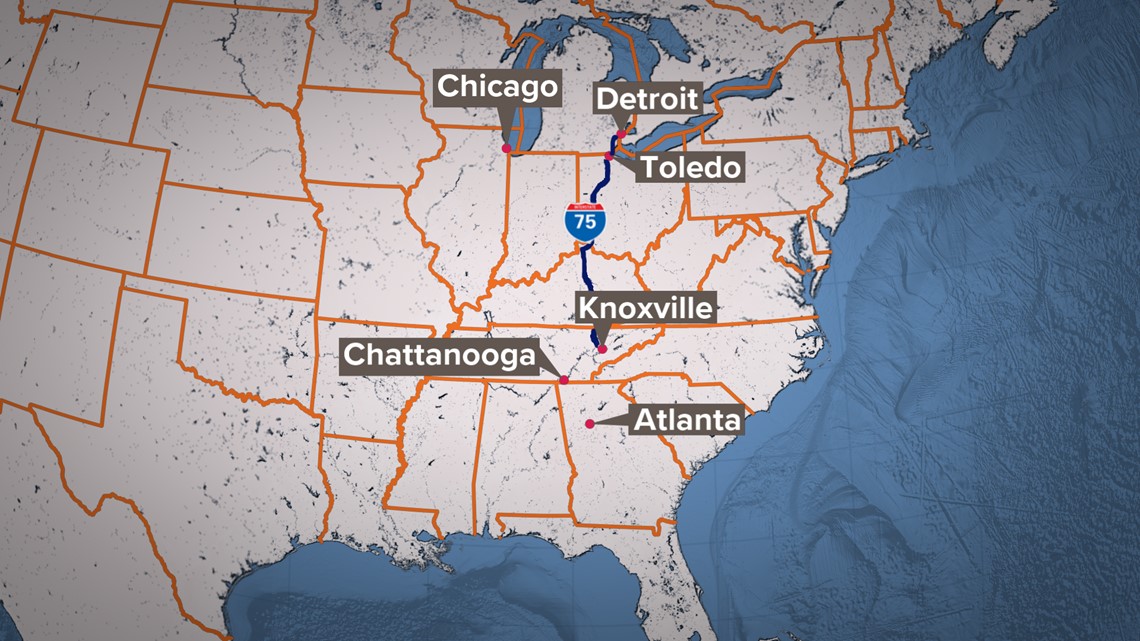

Often, the investigation spans multiple states to go as far up the ladder as possible and charge high-level drug dealers with murder.

In 2017, 11 people were charged with second-degree murder in Knox County in connection with fatal overdoses. Some have ties to Detroit, Toledo, Ohio, or Atlanta.

The drug user's cell phone is proving valuable as authorities try to build a case.

“Drug dealers, their communications occur via the phone,” said Tommy Farmer, special agent in charge of the Drug Division for the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation and director of the Tennessee Dangerous Drugs Task Force. “The last source of information or the last person that had contact with them or saw that person is always going to be one of the best sources of information for us to hopefully try to understand and put together the pieces as to what occurred. A lot of times, that last person is absolutely the drug dealer.”

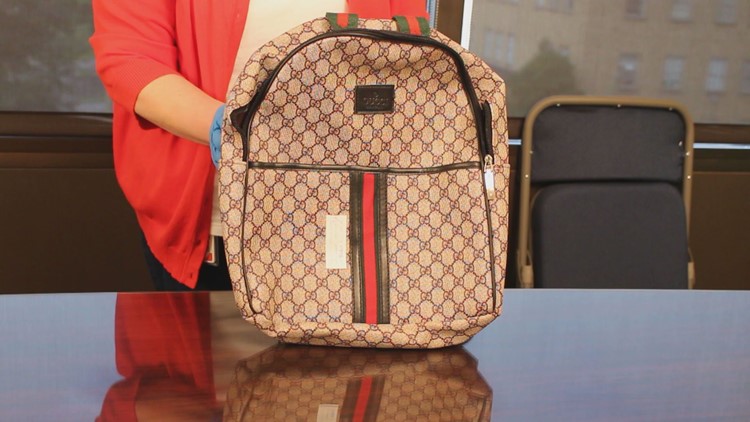

PHOTOS: Tracing An Overdose - the evidence

FINAL TEXTS

Fourteen hours before Lyday was found unconscious in the bathtub, evidence shows, she sent a series of texts. They were the last messages on her phone.

“I got one hundred dollars to celebrate July 4th,” she wrote in the string of messages to ex-boyfriend Justin Lee. “I wanna get this done.”

Around 9 p.m. July 3, Lyday set up a meeting inside the Walgreens near West Town Mall with Lee.

“Are you at Walgreens inside?” asked Lee in a message to Lyday at 8:53 pm.

“About to walk inside in 2mins,” Lyday replied.

Investigators believe the goal of the meeting was to hand off money for drugs.

"Ms. Lyday had met with an individual the night before named Justin Lee and had most likely obtained heroin from him,” said Philip Jinks, an investigator with the Knoxville Police Department Organized Crime Unit who was assigned to Lyday’s case. “Jessica actually walked from her mother’s house under the guise of going for a walk and walked to the Walgreens. Justin met her there and she gave him the money that she had acquired to purchase heroin.”

Lyday and Lee would meet up again an hour later at the Walgreens. This time, investigators say Lee handed off the drugs to Lyday that would cause her death in a matter of hours.

FROM THE SELLER TO THE SOURCE

Now that they had the text messages, the challenge for investigators was to determine exactly where Lee got the drugs that he passed on to Lyday.

“From the original cell phone of Jessica’s, we were only able to identify Justin Lee,” Jinks said. “Jessica Lyday was a human being, she was a person. We all have problems, we all have different issues. Jessica was just a person. She deserved a thorough investigation. She deserved to have some justice.”

Lyday and Lee had known each other for years. But was he the only one responsible for her death? Further up the chain, Jinks knew, was the source of the deadly opiate.

“After I interviewed Justin at his home, I took possession of his phone," the investigator said. "While I was in possession of his phone, the phone received a message from a contact named Slim.

"The incoming text message actually was instructing Justin to check his mailbox.”

Jinks went to Lee’s house and checked his mailbox. Sure enough, there was heroin inside. That discovery helped break the case.

After Lyday and Lee met at the Walgreens for the money handoff, Lee set up a meeting with the contact named Slim, Jinks said.

“I’ll be back at the crib in about 20 minutes say 9 o’clock,” Lee texted.

Within days of Lyday's death, Jinks set up a controlled buy between Lee and Slim. He recorded the call.

“Hey. I’m at my mom’s. Put it in the mailbox, OK? I’m gonna have to go to the hospital so whenever you come by, whenever, just call my phone, whatever, and let it ring once or something,” Lee told Slim.

“Imma be out that way in about 20 minutes,” Slim replied.

At Lee's request, Jinks agreed to deliver another quantity of heroin to Lee’s mailbox. And this time, KPD was waiting.

“The organized crime unit and other officers helping with the investigation were there, we were watching,” said Jinks.

Slim, whose real name was Kenyon Demario Reynolds, tried to run when police tried to stop his car near his home on Morrell Road. After a short foot pursuit, officers took him into custody, Jink said.

Inside Slim’s home, police found $40,000 in cash, a firearm, and evidence of the drugs that killed Lyday. Much of it lay right next to children’s toys.

“One of the children indicated that there was a handgun that was hidden between the mattress and the box spring of Mr. Reynolds' bed,” said Jinks. “He tried to take us to it and show us, but we stopped, that obviously.”

Reynolds refused to tell officers his real name or admit to any crimes.

“The way that he was identified was through fingerprints. The first time I ever heard Kenyon Reynolds speak his real name was when he testified at the trial,” said Jinks. “He was actually living under an alias in Knoxville. He was wanted from another state at the time.”

Reynolds came from Atlanta, obliging with drugs for hungry East Tennessee customers.

“In Knoxville, we’re in a position where I-40 and I-75 intersect -- which is a major north and south interstate through the country and a major east and west interstate through the country,” said KPD Sgt. Joshua Shaffer, part of a multi-agency task force that tracks the opioid market in the Knoxville area. “We’re only 3 1/2 hours north of Atlanta. Atlanta is a major drug hub for this part of the country, and we’re literally, jump on the interstate and jump off of it for that.”

Reynolds was tried for his crimes in Knox County Criminal Court.

He's currently serving at least 30 years in prison after he was convicted of second-degree murder.

Lee was also charged with second-degree murder in Lyday's overdose death. He's awaiting sentencing.

Nothing will ever bring Jessica Lyday back, but the investigation into her death using her cell phone and text messages may have helped save other lives. It got a high-level drug dealer off of the streets, Allen said.

“The one person that has lost their life here obtained their drugs from somewhere. And those drugs came from somewhere, and from somewhere, and from somewhere,” said DA Allen. “If you follow those up the chain, you really get into the dealers, you get into the gangs, you get into people that are making a living by distributing drugs in our community and preying on those who are the users.”

WHO WAS JESSICA LYDAY?

Lyday had battled addiction for years but appeared to be on the right track towards beating her demons right before she died, her mother said.

She'd completed a 30-day residential treatment program months before her death and was scheduled to be admitted to a long-term treatment center in the coming weeks.

Her family says Lyday should not be remembered for the way she died, but rather for the life she lived.

Her mother, August, still keeps notes, drawings, and journal entries made by her daughter.

One note, written just seven months before she died, tells a story of how Lyday believed she was getting better.

“I think about changing my life, my goals, my destiny. I believe in myself. I desperately want to right the wrongs with my mom and be the daughter she can be proud of,” Lyday wrote. “I have a long way to go as far as making things right with myself and with others, but I know I’m on the right path.”

Lyday also loved to sing. She recorded a song about her home in East Tennessee that her mother shared with 10News.

“We never have enough time when we love somebody,” August Lyday said about her daughter. “Make the time count every day with the person that you love, because it’s never long enough.

SEEKING HELP WITH OPIOIDS? HERE ARE THE OPTIONS

East Tennessee is far away from providing all the resources needed to combat the opioid crisis.

But there still are places you can go for help.

The Tennessee Redline, which is funded by the state, offers referrals if you need help with abuse. The number is 800-889-9789, and there's more information available here.

The state also offers guidance on where to get help in Tennessee here.

Another place to start is the Metro Drug Coalition in Knoxville. You can learn about confidential referrals for treatment by going to its website.

New this year, the coalition began Hands of Hope, a mentoring program for first-time moms who are getting addiction treatment or are recovering from addiction. One aspect of the program - helping young mothers stay sober while also raising a Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome baby.

The Knox County Health Department has more information about where mothers can go to get help. Try this link.

The University of Tennessee Knoxville campus also offers numerous places to turn for help in our area. Find out more.

The Partnership for Drug-Free Kids offers strategies and toolkits to help parents address substance use. You can call 855-DRUGFREE or visit drugfree.org.

There are a number of opioid treatment and residential programs in East Tennessee.

One that's specifically designed to help mothers is Susannah's House Mothers in Recovery. It's a licensed outpatient program for mothers with infants or young children who want to be sober.

Here is a link to learn more about Susannah's House.