Cades Cove — A child's prank led to the disappearance of 6-year-old Dennis Martin. Forty-eight years later, the Knoxville boy's whereabouts remain a mystery.

Despite perhaps the largest manhunt in the history of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, searchers came up empty in June 1969.

Hundreds of students, Special Forces, National Guard troops and East Tennessee volunteers spent thousands of hours searching for Dennis. One of the few possible clues: a child's shoe print found in the ground by two old-timers.

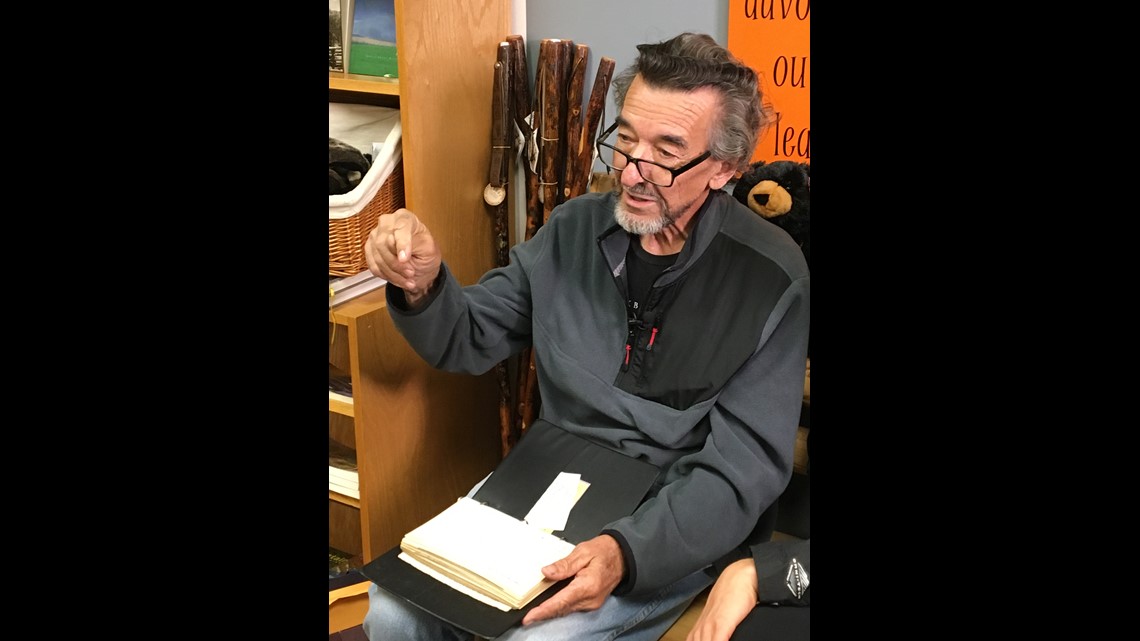

"The FBI said it was a searcher's shoe," said retired Smokies ranger Dwight McCarter, who took part in the hunt for the boy. "But it was a little boy's footprint, a little Oxford shoe like he was wearing. The FBI disregarded it.'

Dennis and his family had spent the night of Friday, June 13, 1969, at the Russell Field shelter in the national park. They were regular visitors.

On June 14, just a few days before the boy's 7th birthday, they went to Spence Field, an open grassy area offering spectacular views along the Tennessee-North Carolina line on the main Great Smoky ridge.

Dennis's father William and some other adults sat southwest of the Anthony Creek trailhead, watching Dennis, 9-year-old brother Douglas and two other boys playing in the afternoon near the top of the trailhead.

Douglas would later tell park officials that he and the other children hatched a plan to play a joke on the grownups: They'd decided to duck down, sneak around and surprise the adults.

Douglas and the other two boys went one way; young Dennis went the other.

It was the last time anyone ever saw him.

The adults had seen the boys split up. But when Douglas and the other two reappeared, there was no Dennis.

According to a Department of the Interior report prepared months later, William Martin became concerned after a few minutes and began calling the boy's name.

He went up the Appalachian Trail to Little Bald, returned and then headed down the trail in the opposite direction to Russell Field.

No Dennis. William Martin kept looking.

Park rangers were alerted about 8:30 p.m., according to the federal report. Hikers in the area said they'd seen no sign of a boy like Dennis wearing short green trousers, a red T shirt and low-cut Oxford shoes.

Alarm spread. Night fell. A rainstorm moved in.

WHERE IS THE BOY?

Over the next two weeks, a massive search played out in the Smokies. Volunteers came from everywhere. Rescue groups from Georgia, Kentucky, North and South Carolina arrived to help.

Dozens of members of the U.S. Special Forces from Fort Bragg, N.C., who were on maneuvers in the Nantahala Gorge came over to help.

Two Huey helicopters flew up from Dobbins Air Force Base in Atlanta. A landing site was set up in Cades Cove. Rangers controlled traffic at the Townsend Wye so the search could proceed without interference from curiosity seekers.

The ranks of the searchers swelled: 300 on Monday, June 16; 365 on Tuesday, June 17; 615 on Wednesday, June 18; 690 on Thursday, June 19; 780 on Friday, June 20.

On Saturday, June 21, an estimated 1,400 people including soldiers, college students, Boy Scouts and medics were out looking for Dennis. Two Army Chinook helicopters flew some searchers in.

They'd saturated the area within a one-mile radius of Spence Field, according to the report. They'd combed area ridge tops and stream drainages.

Many days brought frustration.

Rain and low clouds often hampered progress. Searchers were carted up and down the Bote Mountain road, which became tough to drive on.

On June 18, a single-engine U-10 airplane outfitted with a loud speaker system was brought in. The idea was to fly William Martin around so that he could call out to his boy.

But when the plane landed in Cades Cove the rear landing gear hit a rock that pierced the rear stabilizer, the report states. The plane now wasn't usable. After it was fixed, it had to go back to its base.

The next day, the fifth day of the search, William Martin went up in a Tennessee Highway Patrol helicopter. He flew over the search area, using a small bullhorn to call out to Dennis.

The effort proved futile, however, "as he could not be heard over the helicopter's engine noise," according to the report.

On another day, a boy wearing a red T shirt and off-green shorts was spotted walking in a Cades Cove campground. It turned out his name was Michael and he was from Kansas. Rangers asked his parents - in light of the ongoing search - to please change his shirt.

Still, the well-intended offered hope and help. Hiking clubs pitched in. Ladies brought meals so searchers could eat.

Psychics including the nationally recognized Jeane Dixon offered visions of where the boy could be found. No lead was ignored.

On June 22, Park Superintendent George Fry joined other officials in a meeting to discuss how to proceed.

Authorities determined they'd covered a general search area of some 56 square miles and an"intensive" search area of about 12.5 miles.

"Nothing at all had been found," the September 1969 report stated.

So everyone agreed to start over. Searchers would be dispatched the next morning to Spence Field and they would check the area once again.

And again heavy rain moved in.

LESSONS LEARNED

On the afternoon of June 29, two weeks and a day after Dennis vanished, William Martin and his wife met with rangers and an FBI agent at the Cades Cove operations center. The chief ranger told the Martins they were ready if necessary to have three of their "best men" keep searching. There wasn't much evidence of a kidnapping, but the investigation into Dennis's disappearance would continue.

An hour later, the Cades Cove center was shut down.

For the National Park Service, the search had involved an estimated 13,430 search hours. Costs for "personal services" and equipment totaled about $50,584, according to the report.

The Army and Air Force had conducted more than a thousand sorties. More than 50 rescue squads had helped, putting in an estimated 69,811 vehicle miles.

Multiple restaurants and area churches provided food. The U.S government had provided helicopters and pilots, boats and operators, fuel and air communications.

Looking back, Dwight McCarter thinks the search, while well-intended, ended up hurting the best efforts to find the boy.

With so many searchers tromping around the grounds, valuable clues that could have been tracked ended up being trampled and destroyed.

"It messed up all the tracks," he recalled. "If you're a tracker, that's the worst thing for you to do," McCarter, 73, said.

Dennis Martin's was the first search that McCarter was involved in in the park. At the time he'd only been with the Park Service a few years.

During his decades in the Smokies, McCarter took part in dozens of searches. Having learned tracking tips from his grandmother as a boy, he became proficient at finding people others could not.

Later on in his career, as he gained seniority, experience and respect for his tracking skills, he'd be able to direct the search for missing people in the Smokies.

But in 1969 he was still relatively new to the park staff. It wasn't his place to tell others what to do.

All these years later, there's no telling where the child's remains are, assuming he died in the park. With the passage of time, layers of forest debris have piled up - maybe an inch a year.

"So you can imagine. Dennis was lost in 1969. This is 2017," McCarter said.

"Where would you look?"