About 90 minutes into our NBC News coverage of 9/11, with the eerie, almost slow-motion television images of the fatally wounded twin towers dominating every television screen, I thought, “My God, is this our Pearl Harbor?”

There were so many similarities and yet so many differences.

It was a bold, brutal sneak attack for which we had no warning until the first airliner crashed into the upper reaches of the south tower.

In rapid succession, the Pentagon was attacked by a hijacked American Airlines flight and a United flight went down in Pennsylvania after a passenger revolt.

We later learned the CIA and other Washington intelligence agencies had spent the summer in states of high anxiety after picking up signals that al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden were planning a strike against the U.S.

In short order, America was at war in Afghanistan and Iraq against jihadist groups and the regime of Saddam Hussein.

Seventy-five years ago on Dec. 7, 1941, a surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in Honolulu stunned military commanders on that sunny Sunday morning, even though there had been warnings as early as January of that year the Japanese could be planning such an ambush.

In the autumn of 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt was officially warned the prospects of a Japanese attack were ever greater.

On the day of the Japanese assault, two forward American observers warned that a squadron of planes was fast approaching Hawaii but their commander waved them off, explaining it was a formation of U.S. bombers being ferried from San Francisco.

In fact, it was a flight of Japanese fighter planes and bombers launched from carriers northwest of the island chain when U.S. military commanders had reinforced vigilance to the southwest, guessing wrongly any Japanese assault would come from that direction.

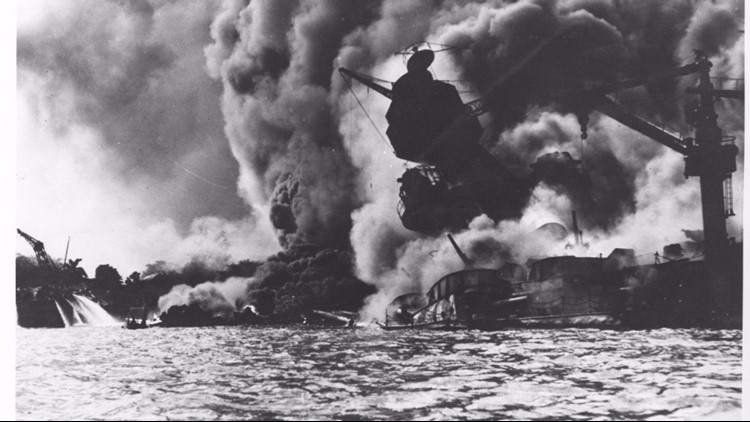

The assortment of U.S. battleships, destroyers and cruisers were anchored bow to stern in the warm waters of the harbor, a cozy arrangement that served the attackers well. On land, American fighter planes were similarly arranged. Parked wingtip to wingtip they, too, were an inviting target.

These inexplicable command decisions and catastrophic miscalculations converted the American battleships, aircraft carriers, destroyers, airfields, fighter planes and bombers into a shooting gallery for the waves of Japanese aircraft.

Because it was Sunday morning, sailors were sleeping in or still ashore from the night before.

As a decorated Japanese fighter pilot named Mitsuo Fuchida led the attack, he shouted into his radio TORA, TORA, TORA — which translates to Tiger, Tiger, Tiger. The killing began.

American survivors I talked to 50 years later all had terrifying experiences and a common memory. They repeatedly referred to the bright-red circle against a white background on Japanese planes not as a sun but a “meatball.”

Despite the heroic efforts of American sailors, commanders, pilots and even galley hands, the Japanese prevailed in two waves of attacks for two hours and then returned to their fleet, where their commander made a huge mistake in what had been a textbook military operation. Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, the Japanese officer in charge, canceled a third wave of attacks, worried the Americans had by 10 a.m. organized themselves for a devastating counterattack.

(The Japanese war planners were helped by the refusal of many American military experts to take seriously the capabilities of Japanese strategists and warriors, even though the Land of the Rising Sun had been successfully waging war against China for almost a decade.)

The canceled third wave left intact Pearl Harbor’s impressive ship rebuilding facilities, resources that proved invaluable in reconstituting the damaged fleet for the hard days ahead. Nonetheless, the two raids were devastatingly effective:

• 2,403 American lives were lost.

• 21 ships were sunk or badly damaged.

• 188 planes were destroyed.

Pearl Harbor and its environs were smoldering ruins, a shocking contrast to the tropical paradise they had been hours earlier.

On the mainland, as news trickled out via radio bulletins and word of mouth, the nation was stunned.

Movies were interrupted and all military personnel were told to report to their bases immediately. San Francisco and other West Coast cities hunkered down and curfews were imposed as rumors spread the Japanese were headed there next.

In large cities, small towns, isolated farms, ranches and Indian reservations, a wave of shock gave way to a fierce determination to fight back. Overnight pacifists shed their anti-war sentiments and reconstituted their attitudes to fit the urgent need for a new warrior class.

In the White House, Roosevelt assembled his Cabinet and set in motion the decisions that led to the largest military buildup in history.

He had been quietly preparing for war in Europe against the Third Reich. Now it would be a war on two fronts, for which the U.S. was woefully unprepared. We were not a major military power that day. The urgency and scope of military expansion now seemed ludicrous.

At the beginning of the 1940s, Romania and Portugal had more men in military ranks than the United States. No other country, though, had the financial and manpower resources, the industrial capacity of the U.S. — and the attack on Pearl Harbor unleashed what came to be called “the arsenal of democracy.”

No one knew that better than British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who received news of Pearl Harbor at a Sunday night dinner with American diplomats at his country home. He was saddened by the devastating blow against his friends but also relieved because, after the terrible trials of hanging on against Nazi marauders in Europe, he now had a powerful partner with unparalleled resources. As he wrote later, that night he slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.

There would be little sleep for Roosevelt. He had a speech to deliver Monday morning, one that would become the first salvo from the commander in chief in World War II. Its opening has never lost its emotional and historic impact.

“Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the empire of Japan.”

He described how the attack came as the U.S. was in talks with the Japanese government to maintain peace in the Pacific. Then he ticked off Japan’s other surprise attacks the day before — against Malaya, Hong Kong, Guam, the Philippines, Wake and Midway Islands.

It was an eloquent call to arms and launched the U.S. into history’s greatest war when Germany declared war on America four days later.

Now, 75 years later, Japan and Germany are allies of the U.S.

As for Pearl Harbor, the scenic, sunny alcove in the Pacific is at once a tale of unexpected treachery, failed vigilance and, above all, individual heroism and the power of America’s unleashed moral might.

It was the birthplace of what I came to call the Greatest Generation, the American men and women who went to war against the madness of Nazi Germany and imperial Japan and saved the world with their selfless and heroic actions on the home front as on distant battlefields.

Brokaw is the former managing editor and anchor of NBC News and a best-selling author whose books include “The Greatest Generation,” which chronicles the lives of those who served in World War II.