Peter Lillelid doesn't remember what the killers did to him and his family.

He has no recollection of how six young Kentuckians met the Powell residents at a rest stop off Interstate 81 in Greene County on April 6, 1997, how they forced them into their van, followed them to a quiet road off the Baileyton exit, lined them up along a ditch and them shot in the night with two pistols.

Peter himself was shot twice, losing an eye and suffering permanent neurological damage from another bullet fired into his back. He was only 2.

But much of East Tennessee remembers. It's marking the killings of Vidar, Defina and Tabitha Lillelid with the passage this week of the crime's 20-year anniversary.

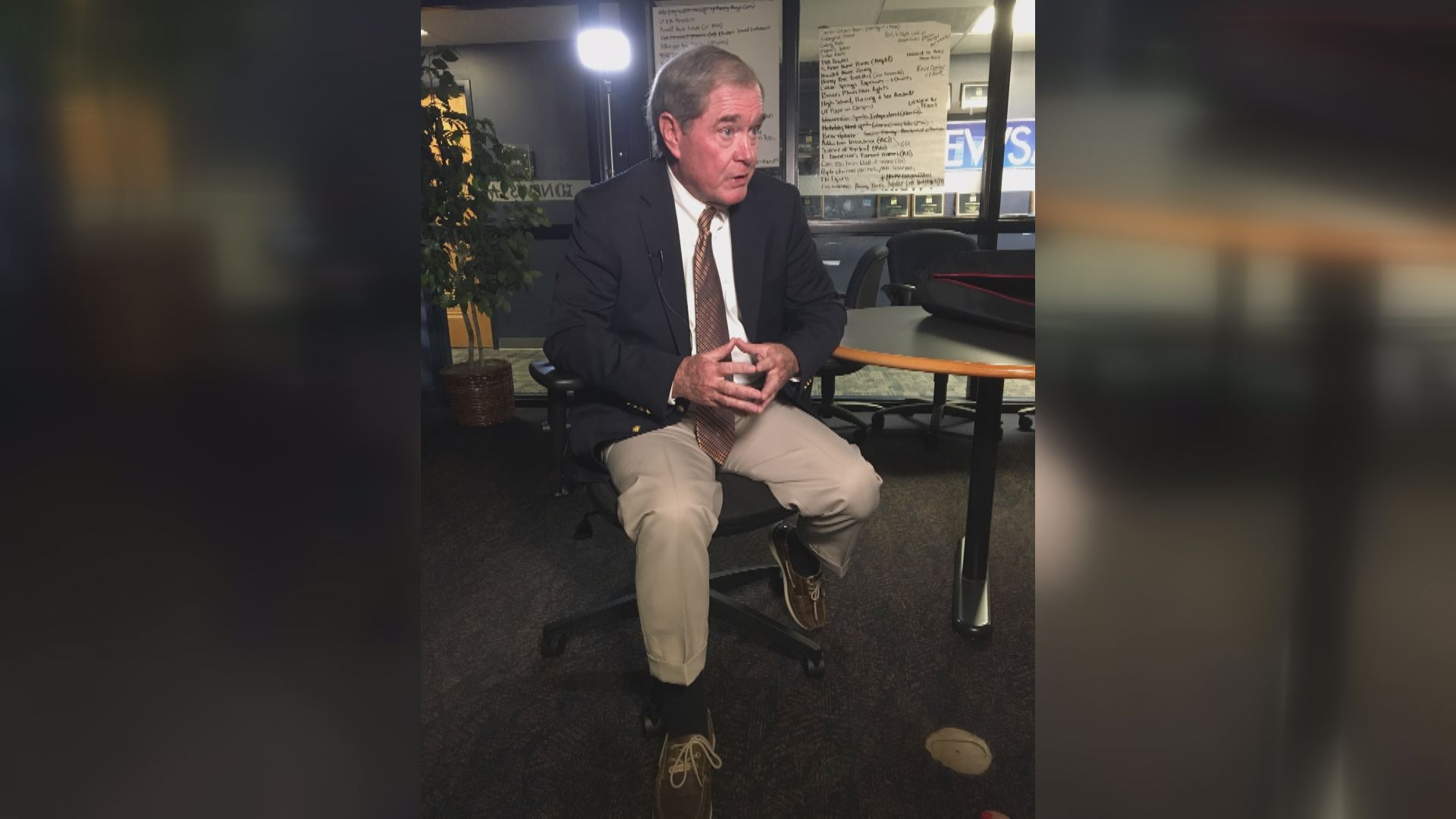

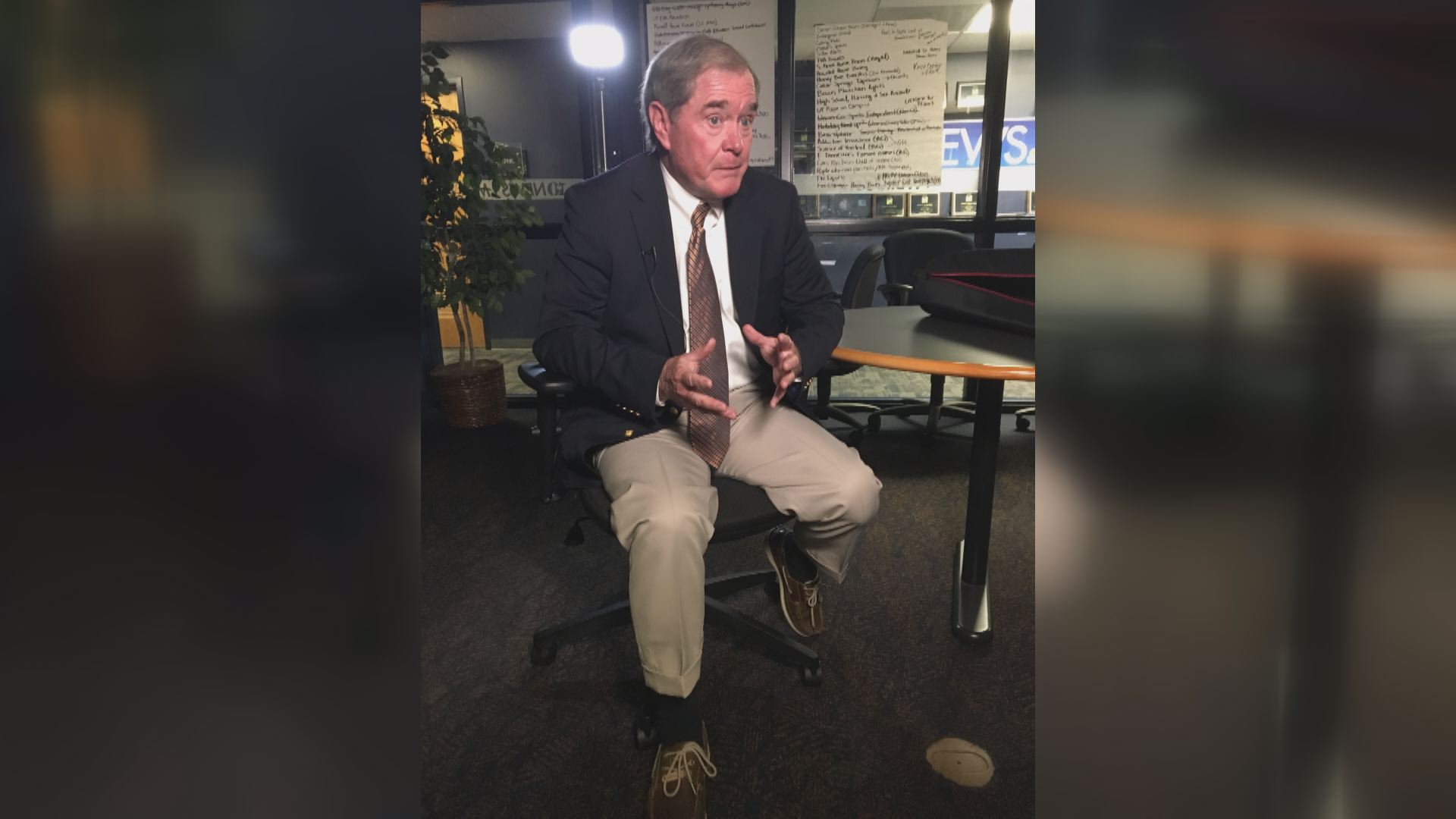

Greene County authorities who worked the case remember. Berkeley Bell, then the district attorney general who prosecuted the case, recalls it well.

So do journalists who reported on the horrifying details of that triple killing and attended the 1998 sentencing hearings at which the six ultimately agreed to plead guilty and spend the rest of their lives in a Tennessee prison.

Gina Stafford, who covered the case for the Knoxville News Sentinel and befriended Peter and his extended family, said the young man is happy, well-adjusted and content to live thousands of miles away among relatives in Sweden.

Stafford, now a spokeswoman with the University of Tennessee system, spoke by phone late last month with Peter on behalf of 10News. She said she asked him if he wanted to say anything to the people in East Tennessee who have thought about him and wondered how he was doing, 20 years after his family was attacked.

"He said, 'Not really, I feel my life is what it is, and I'm happy with it, but it's touching to know there are people somewhere else that you can't meet and know by name who care a lot about you, and I appreciate that. It's nice to hear people still care.' "

Bell, who had a little boy at the time of the killings, thinks about Peter and wonders how he's doing, how the shootings affected him.

He'll never forget what happened to the Lillelids. For Bell, there's one word to describe what happened to them: evil.

"It was just a tremendous tragedy for absolutely no purpose whatsoever," he said.

Thrillseekers on the highway

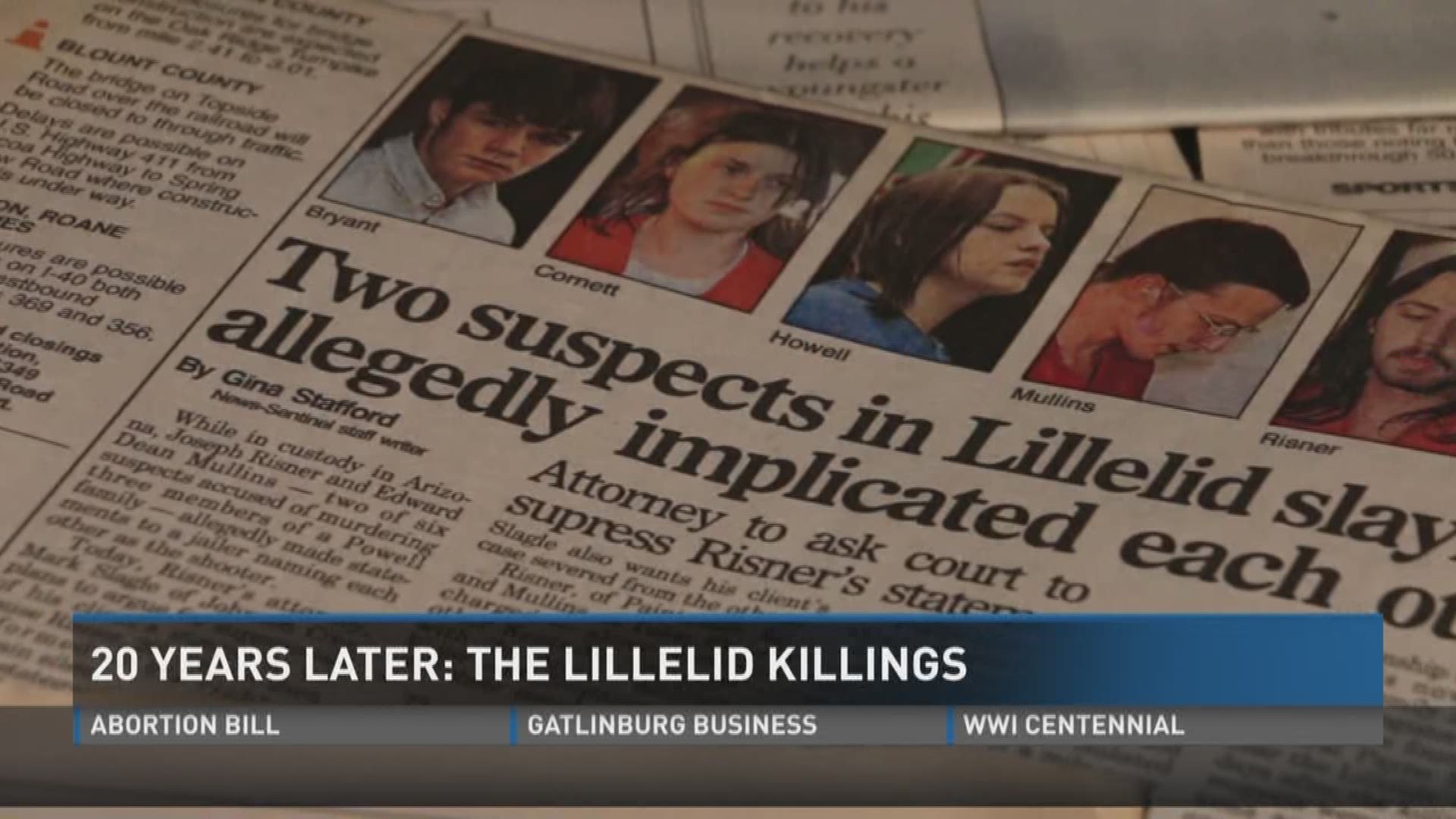

In the spring of 1997, Joe Risner, 20, Natasha Cornett, 18, Karen Howell, 17, Crystal Sturgill, 18, Dean Mullins, 19, and Jason Bryant, 14, were living in far southeast Kentucky in towns like Paintsville and Pikeville, close to the West Virginia and Virginia lines.

Some were friends, some were loosely acquainted. Authorities allege they were allied by boredom, recklessness, a sense of isolation, unhappiness with their family life, a twisted desire to do something that had meaning.

A few even believed in witchcraft and the occult, and some were attracted to the black "Goth" look, according to Bell. Cornett had cut herself, and she fancied Satanism.

In early April, they stole a 9mm and a .25-caliber pistol and hit the road in a beat-up Chevrolet Citation. Cornett, according to authorities, was fascinated with movies like "Natural Born Killers" and boasted of perhaps staging a series of crimes just like the homicidal actors in the film.

Cornett, in fact, appeared to be the group's ringleader.

They arrived at the rest stop off I-81 in Greene County on the afternoon of April 6.

By coincidence, the Lillelids had stopped at the same place.

"It was a Sunday evening and they had gone to Johnson City earlier that day for an all-day workshop for members of the Jehnovah's Witness faith, and at the end of that workshop they were driving back home to Powell," Stafford recalled.

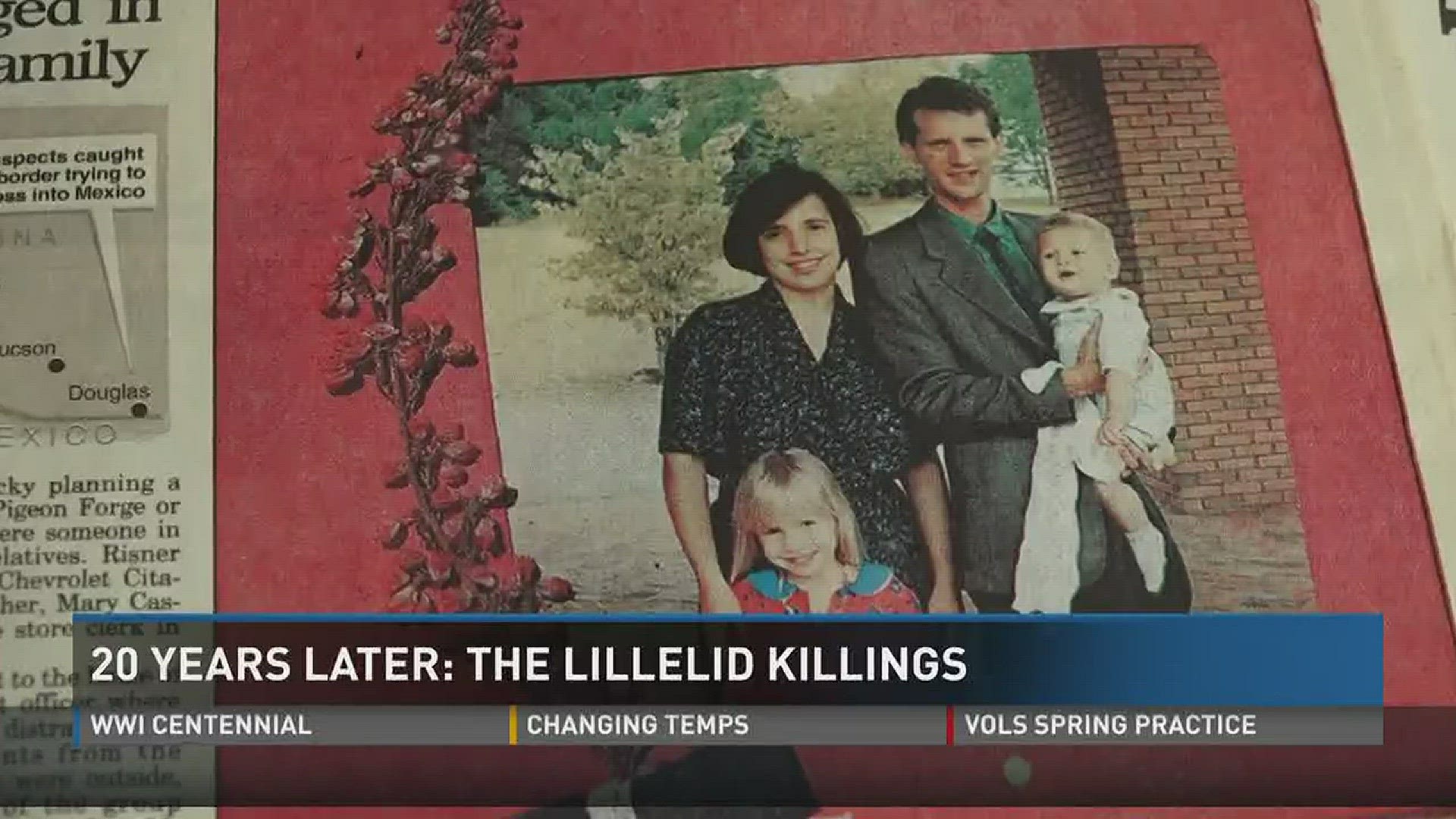

Vidar, a native of Norway who had moved to the United States intent on a better life, was 34. Delfina'a family was from Honduras. Delfina, 28, had met Vidar in South Florida.

They'd ultimately settled in East Tennessee. The Lillelids had saved what they could, but they didn't have much money. Vidar worked as a bellhop at the Holiday Inn near Cedar Bluff Road in West Knoxville.

Delfina and Tabitha, 6, encountered Howell and Cornett in the restroom.

The family and some of the Kentuckians struck up a conversation. Vidar talked about his religion and the importance of being saved.

Risner testified later that they were desperate to get a replacement vehicle because the Chevy wasn't going to last much longer. The Lillelids appeared to offer the group an opportunity.

Risner said he quietly showed Vidar the 9mm tucked in his pants. He said the group wanted the Lillelids' aging Dodge van. No one would get hurt, he said, but they would all have to leave together to find a place where they could take over the van.

With Vidar at the wheel of the Dodge, the Lillelids and the Kentuckians headed in the two vehicles to the Baileyton exit. They drove down Payne Hollow Road to a spot that looked remote, although residents lived not far away.

What happened next - and who did what - has never been fully explained or made exactly clear. Most of the killers accused Bryant of shooting the victims.

Neither Bell nor the police believe he acted alone. Bryant had the .25-caliber pistol, but Risner had handled the 9mm, records show.

According to Bell, no one that day was innocent. Authorities came to believe that the group made sure everyone took part.

"It was part of an initiation, for lack of a better way to put it," he said. " 'If you're going to be in this group, you're going to have to go through this. This is us.' "

The famly was made to get out of the van and stand in a ditch. Most of the group agreed that Vidar and Delfina pleaded for their lives, especially those of the children.

Risner would later testify that Bryant began shooting.

Vidar was shot six times; Delfina was shot 8 times, records show.

Bell recalled that bullets were fired into Vidar and Delfina that formed the shape of a pentagram. Another bullet hit Vidar in the eye.

One bullet hit Tabitha and two hit Peter.

A neighbor later recalled hearing gunshots and the happy sounds of people playing. But police didn't think that was the Lillelid children. They theorized the neighbor heard some of the Kentuckians, perhaps enjoying the crimes they were committing.

Bell said the killers "arranged" the Lillelids' bodies in the muddy ditch.

"They laid the parents out, laid the children over them in the form of a cross. Then they got in the van, turned around, came back and intentionally and maliciously ran over them," he said.

Tabitha and Peter still were alive, although Tabitha would die the next day at a Knoxville hospital.

Leaving the blue Chevrolet behind, with its headlights still burning, the Kentucky six headed out into the night.

A lifetime in prison

The Kentuckians' ride didn't last long.

On April 8, they were caught in the Lillelids' van trying to get into Mexico at the border at Douglas, Ariz.

One of the young men remarked to an officer after their capture that he was a "killer," according to Bell. Prosecutors saw the admission as a key piece of evidence in their pursuit of the death penalty, although it ended up proving a false hope.

Back in Tennessee, police traced the blue Citation back to Risner's family, and they quickly pieced together who all likely was involved in the Lillelids' killings. Shock descended on East Tennessee as people began to comprehend the depth of the attack.

Tabitha did not survive her gunshot wounds, dying April 7, 1997, at the University of Tennessee Medical Center.

Peter, found crying and muddy with his mother's body, survived at the hospital, although he had suffered serious injury and lost an eye from a gunshot fired to the back of his head.

The killers were brought back to Greene County. A mass of angry people greeted their arrival at the Greene County Courthouse, shouting and calling for justice. In Knoxville, a store hung six nooses, symbolic of how many wanted them to be punished.

But as the months progressed, Bell found himself with a problem.

There was obvious evidence of the six's involvement in the crime -- the van, personal items of the victims that some of the young people had kept with them.

But the defendants hadn't confessed to the exact roles that all had played. Many pointed at Bryant as the lone shooter. At age 14, he couldn't face the threat of the death penalty because federal law spares juveniles from facing the threat of execution.

Bell, who had announced he would seek death against the adults, saw that as a deliberate "tactic" by the group.

The prosecutor's case suffered a serious setback when the lawman to whom one of the adult defendants had made the "killer" remark turned out to have a credibility problem. He had a criminal record. Defense attorneys could raise doubts about his honesty at trial.

Finally, in 1998, the state presented an offer: Bell would accept a deal if all six pleaded guilty to murder and other charges and accepted a sentence of life without the chance for parole. It was an all-or-nothing bargain.

The Kentuckians took it.

Stafford later met with Sturgill, Cornett and Howell in prison. They said they were sorry for what happened. But they still wouldn't budge about who did what, other than to point the finger at Bryant.

As she sat there looking at them, Stafford was struck at how they seemed unaware of what they were facing - death behind prison walls.

"They were tearful and expressed a lot of remorse and said they wished they hadn't made the bad choices they did that put them in this place," she recalled.

At least some of them still appear sorry that they ended up in prison.

Last month, Howell and Sturgill wrote letters to the Greeneville Sun.

Sturgill wrote that she had spent "the past 20 years trying to atone."

She continued: "I am no longer the broken shell of a girl who was too afraid to stand up on that gravel road. I still struggle with the scars that so many years of abuse left me with, but the woman I have grown into would have done more than hide her face and cry that day. She would fight for what she knows is right, even if that put her in the path of danger."

Howell wrote that her tears "still fall for the victims of the crime. There is not a day that goes by that I do not think of Peter Lillelid and wonder how he is doing."

But Howell doesn't think she should spend the rest of her life in prison.

"I don't believe I deserve to die in prison for murder," she wrote. "I never thought or ever wanted or intended that someone would die. That's never who I was, then or now. In my own heart I have never stopped hoping and believing that maybe one day I'll have the chance of walking out of prison. I've always hoped that (Peter's) heart is beautiful and that the tragedy of what happened to his family didn't cast a shadow over it."

Howell and Bryant now argue that a 2012 federal court decision should be considered in their favor.

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court found that courts couldn't make mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles. The court found that the child's circumstances had to be carefully weighed.

Howell is scheduled to appear April 21 in Greene County Criminal Court to pursue her case.

Cornett, long considered the ringleader in the spree that led to the Lillelid killings, has faced more trouble in prison.

In August 2001, authorities allege, Cornett tried to help her friend Christa Gail Pike, who is on death row for murdering an 18-year-old woman in Knoxville in 1995, kill another woman in prison. Pike was convicted in the attack; Cornett was not charged.

Life after the killings

Today, Peter Lillelid lives in the Stockholm, Sweden, area, and is interested in a career perhaps in insurance or business. He graduated from high school in 2014 and went on to a professional school.

He can walk by himself, although one of his knees doesn't flex easily, Stafford said. While at home, he walks unaided. But when he's out and about, he'll use a wheelchair to help get around.

After Peter's parents and sister were killed, members of his extended family went to court to determine who should raise the little boy. A Tennessee judge determined it would be best for him to go live with one of his father's sisters in Sweden.

Stafford traveled to Sweden and wrote a series of stories on Peter's recovery for the News Sentinel when he was still a boy. 10News also did stories about him from Sweden 10 years ago.

In 2007, Peter and members of his family also came to the Knoxville area, spending some time in a cabin in the mountains, Stafford said. She and her husband, Bill Phelps, spent time with them.

Stafford and Peter also are friends on Facebook.

"He's very personable, bright, kind, witty," Stafford said. "He has a great personality."

Stafford said she recently learned that Peter had swung through Knoxville last summer while on a low-key visit to the United States. He ended up meeting a Knoxville police officer who had guarded his door at the medical center after the child was shot, Stafford said.

They had their picture made together.

The officer told him he just wanted him to know he'd always thought about him and had been glad to stand watch to ensure no one came to hurt him.